By Suresh Nair

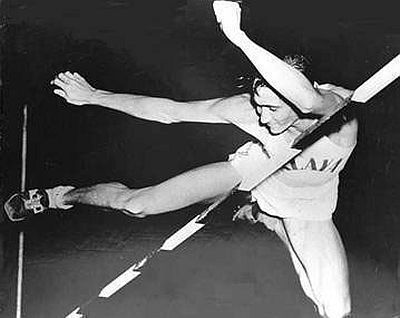

Lloyd Valberg. Tan Howe Liang. Tan Eng Yoon. “Uncle” Choo Seng Quee. Natahar Bava. Canagasabai Kunalan. Syed Abdul Kadir. Chee Swee Lee. Patricia Chan. Ang Peng Siong.

Just to name 10 Made-in-Singapore sporting icons. And it begs the question: Are they sporting heroes or forgotten men and women?

As I went through the 487-page, 2005 edition of Singapore Olympians, I came across 150 Singaporeans who took part in the Olympic Games from 1936 to 2004. “This book lights the flame and sparks dreams of glory in future generations of athletes,” says Deputy Prime Minister Teo Chee Hean, who calls it “the story of Olympic sports in Singapore and its impassioned athletes”.

Yes, after covering sports for more than three decades, I realised that the road to sporting success, like the ascent to political power, is never an easy one.

On its most personal level, the journey requires tremendous faith and dedication, great sacrifice by athletes and their families. And the monetary rewards, up to a few years back, were a pittance. Nor was there much by way of recognition.

In a foreword to Singapore Olympians, Jacques Rogge, the now-retiring IOC (International Olympic Committee) president, says sporting icons are modern-day heroes who motivate young people, inspiring dreams of Olympic success and reaching pinnacles of glory.

But the big questions is: Does Singapore truly value its sporting statesmen as it endeavours to build a sporting culture, with professionalism coming to the ranks of football, table-tennis, athletics and badminton, primarily fired by foreign talents rather than home-grown prodigies?

I remember how “Uncle” Choo Seng Quee, who guided the Singapore, Malaysian and Indonesian national football teams in the 1970s and 80s and was recognised as the most successful post-war regional coach, believed in patriotism and playing for the flag. The Lions were made to sing Majulah Singapura at the break of dawn before training started at Jalan Besar Stadium. The Singapore flag and crest were tools he used to motivate and inspire players.

Semangat, the Malay word for inner strength, was the most passionate word used by “Uncle” Choo — something which is sorely missing in the current foreigner-based era of sports here, where international successes in table-tennis or badminton are carved out by highly-paid foreign sports-labour.

An uncompromising disciplinarian, “Uncle” believed that a player must be prepared to make sacrifices, without which no success can be achieved. A match-winning team was one that was disciplined and had players who put their hearts and souls into the game in pursuit of glory, for either club or country. Not for the dollars and big bonuses they crave for now with zero Asian-class glory.

An iconic coach, “Uncle” Choo steered Singapore to triumph in the Malaysia Cup in 1964 and 1977. He won the cup with classic teams skippered by Lee Kok Seng in 1964 and Samad Allapitchay in1977. And true to his no-nonsense trademark, in the 1977 cup victory, an extra-time 3-2 win over Penang, “Uncle” daringly withdrew the skipper, midway through the match, because he didn’t show the “semangat” spirit.

Natahar Bava, likewise, brought glory with his inspiring patriotism when Singapore won a historic 1978 Malaysian Rugby Union (MRU) Cup victory in the annual tournament after 44 years of participation under the label, Singapore Civilians. Bava’s boys drew on a tsunami wave of “semangat” to turn the tables on the marauding Royal New Zealand Infantry Battalion (RNIR).

The same year Singapore finished No 3 in Asia after powerhouses Japan and South Korea — the best showing ever by an all-local Singaporean team! For its efforts and achievements, the Singapore National Olympic Council (SNOC) awarded a “Grand Slam” of three major awards – “Sportsman of the Year” to pack leader Song Koon Poh, “Coach of the Year” to Natahar Bava and the players hailed as “Team of the Year”.

Yet, to show how current repugnant political ego overrides historical glory, there’s no mention of Bava’s heroics on the Singapore Rugby Union (SRU) website. Click on http://www.singaporerugby.com/p/history.html and you see the rugby register, recorded only from 1995. (If you click on http://www.mru.org.my/ver3/ the MRU website, you view some genuine history with the game first started in 1823 when William Webb Ellis spontaneously decided to spoil his schoolmate’s soccer game by picking up the ball and running with it towards the goal line!).

If I had a magician’s wand or a crystal ball, I’d like to see the so-called history of Singapore sports rewritten and the heroes of yesteryear genuinely recognised with lasting memorials – for example, with a football stadium, hockey astro-turf pitch, athletics arena or sports building named after them.

If there can be a Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (in YIshun New Town) or a Tan Kah Kee MRT Station (in the new Downtown Line in 2015), why not a Tan Howe Liang Auditorium, where youngsters can flex their muscles and train to be future weightlifting champions, emulating Singapore’s first Olympic silver medallist at the 1960 Rome Games?

Should we not have a Choo Seng Quee Stadium to honour the legendary football coach who died 30 years ago after inspiring the Lions to success with his fiery patriotism? And how about an Ang Peng Siong Pool to continue the waves made by the semangat-bred swimmer? Let’s not forget he was the world’s fastest in the 50-metre freestyle in 1982 and regarded as Singapore’s most successful swimmer, having won the ‘B’ final of the 100m freestyle at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games.

They cannot be forgotten heroes. Their success stories along with their sporting paraphernalia cannot just be left within the cold walls of a sports museum.

The 10 Singapore sporting legends I mentioned here, and many more deserving luminaries, must be showcased publicly, perhaps even with giant-sized iconic figures at the upcoming Sports Hub expected to open next year.

But if the current trend prevails and only lip service paid, without the revival of the semangat spirit among the bureaucrats, the sporting stars of yesteryear may well just be curiosities and conversation pieces.