By: Thum Pingtjin

The following is the text of my remarks at the Singapore Theatre Festival’s Art and Life Session #03, “History, His Story, Whose Story?”, Sunday 24 July 2016. My fellow speakers were Tan Pin Pin, Sonny Liew, and Jason Soo, and the panel was moderated by Alfian Sa’at. Due to time limitations, I left out the text marked in square brackets.

Our assumptions about our past shape how we read the events of today. Not just that, but they are used to justify certain policies, and argue for certain values which shape our society.

Last week, Daniel Goh mentioned the 1964 riots. I disagreed with his characterisation of the riots and tried to argue with him about it. I don’t think he understood the point I was trying to make, but to be fair, I didn’t make it very well. Which was that context matters in how we understand history. Framing matters in how we understand history.

And how we understand our own history affects how we understand events today. Calling the 1964 riots “race” riots implies that it was a fight between two races, between Malays and Chinese, and it is routinely trotted out to explain why Singapore has extremely fragile race relations, why we need to clamp down on any discussion on race, for fear of upsetting a fragile racial balance.

The problem is, to call it a race riot is to neglect the fundamental cause of the riot. Which was politicians manipulating the race issue for their own political gain. And by misunderstanding it, we then apply the wrong lessons to Singapore today.

The problem is, to call it a race riot is to neglect the fundamental cause of the riot. Which was politicians manipulating the race issue for their own political gain. And by misunderstanding it, we then apply the wrong lessons to Singapore today.

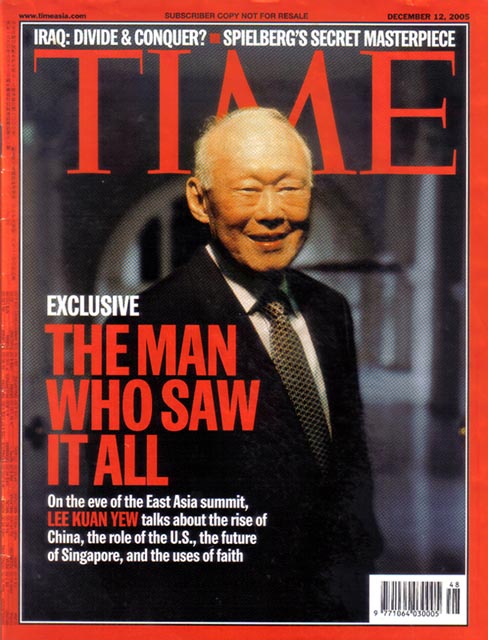

So let me briefly explain the root cause of the riot. It starts in 1961, as Lee Kuan Yew was losing popularity in Singapore. He was going to lose the next election, and he needed an issue that he could control, to regain popularity, to reassert his authority within the PAP, and to win the next election. And the only issue that he could immediately control was merger.

But the Federation leadership did not want all of Singapore’s Chinese in the Federation. And not because of race, but because of politics. It would dilute the UMNO vote and undermine its claim to power. That’s what they really cared about. So how could Lee change the Tunku’s mind? By scaring him into believing that Singapore’s Chinese were communist and chauvinist, and were about to kick out the PAP and elect a militant communist, Pro-China government.

This was totally untrue – it was Lee Kuan Yew, not the PAP Left, who was in an active conspiracy with the Malayan Communist Party. But Lee argued that the only way to save Malaya from descending into civil war was merger, for the Federation to take in Singapore and assume control of Singapore’s security. So it is Lee who plays the race card first, painting a false picture of Singapore’s domestic political situation to scare the Tunku and the UMNO leaders.

Naturally when the Tunku finally agrees to merger, he wants a form of merger that guarantees two things. That Singapore’s citizens cannot vote in the rest of Malaysia, and that Singapore political parties do not run in the rest of Malaysia. That way, Singapore’s “dangerous” Chinese are quarantined in Singapore. And Lee agrees to this situation because he needs merger to save himself.

He agrees that Malaysia must always be a Malay country. He does not care that merger, as constructed, is a form of semi-colonialism for Singapore, because we are under-represented in the Dewan Rakyat (the Malaysia parliament).

In Singapore’s 1963 Elections, UMNO politicians actively campaigned in Singapore for the Singapore UMNO, arguing that Singapore’s Malays are second-class citizens. UMNO Secretary-General Syed Jaafar Albar came to Singapore and called the PAP Malay politicians un-Islamic and traitors to the Malay race. Singaporeans ignored him and every single UMNO candidate lost.

But the next year, Lee uses this as an excuse to break his promise to the Tunku. The PAP ran candidates north of the causeway in the 1964 Malaysia General Election, and Devan Nair won in Bangsar. This is the exact thing that the UMNO leadership feared. And to them it proves exactly the point that Lee had made before merger, that Singapore’s Chinese are dangerous, they cannot be trusted, they will stab you in the back, try to take over Malaysia and end Malay supremacy.

Worse, Lee then forms the Malaysia Solidarity Convention with opposition parties in Malaysia, attacking the one thing that UMNO can never compromise on: Malay supremacy. Lee’s actions embolden the more hardline nationalist elements in UMNO, whom he called the Malay Ultras. Lee became UMNO’s archenemy, and the more Lee tried to address this growing antagonism, whether by conciliation, compromise, or confrontation, the worse it became.

The stress of this period took its toll on Lee in highly visible and destructive ways. Lee found it increasingly difficult to exercise self-control in front of a microphone, and he developed a pattern of making outrageous and inflammatory speeches, which Toh Chin Chye later admitted were anti-Malay.

Lim Kim San, years later, was asked in an interview whether they had asked Lee to tone down his speeches, and he replied: “Oh yes! We did! But once he got onto the podium in front of the crowd, paah, everything would come out. Exactly what we told him not to say, he would say!” [1]

So it in this context of Lee inflaming the racial situation that the 1964 “race” riots happened. Thus, if we simply call them “race” riots then we totally neglect the fact that the conditions for the riots were created by Lee Kuan Yew and inflamed by selfish, short-sighted, racist politicians, on both sides of the causeway, for their own personal ambition.

[And it is because of this whole situation that that Goh Keng Swee desperately opened secret negotiations with UMNO in mid-July 1965 to arrange separation. He wanted to avoid mutual destruction. And the final formula that both sides agreed on centred on the creation of a lie that would become the foundation of Singapore’s nation-building mythology: the myth that the Tunku expelled Singapore from Malaysia against its will. People today still repeat this myth even though Goh Keng Swee admitted the truth in 1996. Why did he admit the truth? I think it was because 1996 was the year National Education started. Goh felt compelled to finally reveal the truth to avoid the systemic perpetuation of a lie.]

In Singapore’s official history, the riots have been depicted as racially, not politically motivated, because in the immediate aftermath of separation, the government needed to create a narrative which supported its actions throughout Malaysia. It needed to create this idea that the PAP was ultimately correct to aggressively push for a Malaysian Malaysia. It needed to draw distance between Singapore and Malaysia. It needed to rally people with the idea that we are alone, that the world is dangerous, that we need the PAP and we need its repression to keep us safe. Most of all it needed people to forget who was really to blame for the riots: our political leaders, who were supposed to keep us safe but irresponsibly risked our lives for their own political gain.

[But the timing is revealing. The race issue was so dangerous that after the 1964 riots, the government rushed to create Racial Harmony Day in… 1997. If racial tensions were such a big issue, why did it take the PAP 33 years to start Racial Harmony Day? Because 1996 was the beginning of National Education. The reason for the day is not race, but politics.]

Without this myth about the 1964 riots, we realise that Singapore has never had a riot caused primarily by racial antagonism or racial hatred. Without this myth about the 1964 riots, we realise that Singapore has never had a riot caused primarily by racial antagonism or racial hatred.

Do we have race problems? Yes! Of course we do. But this myth prevents us from dealing with them properly. Until you understand a problem, until you are free to discuss a problem, you cannot properly deal with it. This myth justifies the idea that we are somehow stupid about race, that Singapore is fragile, that Singapore’s race relations are fragile, that Malays and Chinese are natural enemies, that it is the government’s oppression that is saving us from fighting each other right now, that we need the sedition act, the GRCs, the Ethnic Integration Policy, the self-help groups, even things like the bilingual policy and CMIO racial categories. Most crucially, this myth tells us that we need the systemic racial discrimination that is built into the system in order for Singapore to survive.

The whole house of cards comes tumbling down if we realise the truth. That it was politicians who caused this situation to begin with. That the real lesson of the 1964 riots is that politicians must be accountable, that we must have checks and balances, that we must have ways of restraining our politicians from unchecked arbitrary executive power. That Singaporeans are better people than what our government thinks we are. We can handle race if we are free to talk about the problem and find our own solutions to it.

We have a choice. We can fight back. And I propose we start in a very simple way. It starts by not calling the 1964 riots “race” riots but the “political riots”. The 1964 political riots. Take back your country’s history.

We have a choice. We can fight back. And I propose we start in a very simple way. It starts by not calling the 1964 riots “race” riots but the “political riots”. The 1964 political riots. Take back your country’s history.

And this is why history matters.

—

Notes: [1] – Melanie Chew, Leaders of Singapore (Singapore: Resource Press, 1996), p. 167.

—

Thum Pingtjin is a Research Associate at the Centre for Global History and coordinator of Project Southeast Asia, University of Oxford.

This article was first published in Mr Thum’s Facebook.