Many years ago, when I was a teenager, I read a British ghost story titled The Whispering House.

In that story, the male protagonist was shot dead by a young woman in the house, because a malign spirit made its inhabitants evil. Unlike that ghost story set in 20th century England, Singapore founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s house at 38 Oxley Road did not make its inhabitants evil. It has, however, set his children against each other.

While he was alive, Lee Kuan Yew espoused Confucian values. Tragically and ironically, before the traditional Chinese Confucian mourning period of three years after his death in March 2015 was over, the quarrel among his children became public.

Since mid-2017, his daughter Wei Ling and younger son Hsien Yang launched on Facebook a series of allegations that their elder brother, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, had behaved improperly over their father’s house. PM Lee denies the allegations.

The dispute has spilled over into a recent penalty against Hsien Yang’s wife, Lee Suet Fern, and a libel lawsuit by PM Lee against Terry Xu, chief editor of the Online Citizen, a local web newspaper. PM Lee is suing Xu for an article in the publication in August 2019 which repeated allegedly defamatory statements by his siblings.

Like The Whispering House, a High Court hearing over the defamation lawsuit on Dec 1 had a hint of the supernatural.

Mr Lim Tean, the lawyer representing Xu, cross-examined PM Lee that day. According to sources at the hearing, Mr Lim, the founding leader of the opposition Peoples Voice party, asked the Prime Minister: “Your siblings are correct, aren’t they, when they say that you wanted to keep the house to inherit Lee Kuan Yew’s credibility?”

PM Lee replied: “I think that is rubbish.”

Inheriting the “credibility” of the late father of independent Singapore is somewhat similar to the superstitions of some South-east Asian peoples, who believe the homes and heirlooms of dead rulers emit supernatural aura which can endow people who come close to them with magic powers.

PM Lee added: “I have been Prime Minister for 16 years and if I still depend on living in a particular house in order to exude a magic aura and overawe and impress the population, I think I am in a very sad state and Singapore would be in a very sad state.”

It is commendable that PM Lee said this. Another Asian leader, Chiang Kai Shek, failed to realise this.

The late leader of Nationalist China had a mausoleum built to his predecessor, Sun Yat Sen, the father of Republican China, after Sun died in March 1925.

I have visited this mausoleum in Nanjing, China, which was completed in 1929. That monument is impressive, set on Purple Mountain with a panoramic view which has to be climbed up many steps. Sun’s mausoleum was near the tomb of Zhu Yuanzhang, the founding emperor of the Ming Dynasty.

Whether there was any aura in Sun’s mausoleum and Zhu’s grave, they failed to save Chiang from losing mainland China to the Chinese Communists, who defeated the Nationalist armies and drove him to Taiwan in 1949.

Thus Chiang forfeited the mandate of heaven to Mao Zedong, who became China’s ruler on Oct 1, 1949. According to ancient Chinese belief, heaven bestowed its mandate on a dynasty to rule China, but if the dynasty was guilty of corruption and misrule, it was justified for rebels to overthrow that dynasty. Chiang had admitted his defeat was due to loose discipline in his Nationalist Party and his party’s inability to serve the Chinese people well.

Chiang heavily milked Sun’s legacy to buttress his legitimacy as China’s leader. When Chiang ruled China, government offices and schools contained Sun’s portraits, to whom people had to bow on certain occasions. Nationalist Chinese banknotes contained Sun’s face. Singapore banknotes do not have an image of Lee Kuan Yew.

Chiang’s failure bears the lesson that a country’s leader should fortify his legitimacy not with monuments but with good governance.

The Oxley saga is partly similar to Gianni Schicchi, an Italian opera composed in the early 20th century by Giacomo Puccini. In that opera, a wealthy Italian man dies leaving a will, then his relatives fight over his house. The opera is named after Gianni Schicchi, an Italian man who changed the will to bequeath the house to himself.

In late November, the Court of Three Judges suspended Suet Fern, a high-powered corporate lawyer, for 15 months. The judges found her guilty of misconduct unbefitting the legal profession, saying she had “blindly followed the directions of her husband, a significant beneficiary under the very will whose execution she helped to rush through”.

In a statement to media, she disagreed with the decision.

Schicchi, who deliberately tampered with a will, is based on a character in the 14th century epic poem, the Divine Comedy, composed by the great Italian poet Dante Alighieri. In the poem, Dante consigned Schicchi to hell for forging a will.

Although the judges temporarily suspended Suet Fern, their judgement said she did not act dishonestly in her dealings with her father-in-law. While the judges found Suet Fern’s legal behaviour imperfect, she cannot be compared in moral turpitude with Schicchi.

The opera Gianni Schicchi ends to the shock of the relatives who were hoping to gain the house, with the house going to Schicchi.

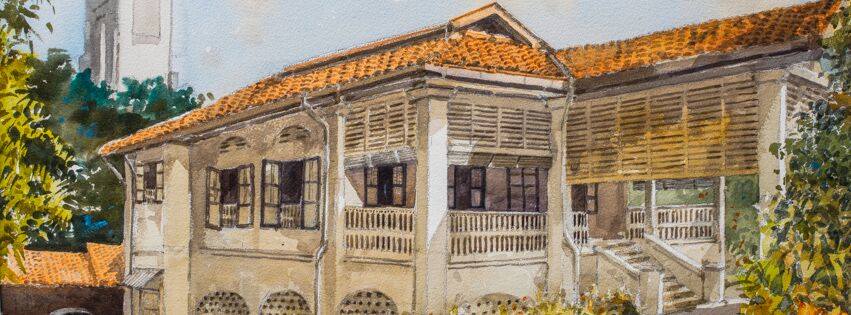

Then again, a Singaporean film-maker can create a fictitious ghost movie based on the Oxley saga. I have never been inside the house but I have walked along Oxley Road. I feel the neighbourhood, with many dense leafy trees, can be spooky at night.

Gentle reader, whether you have any religious beliefs or none, whether you believe in the supernatural or not, the longer and more acrimonious this Singapore drama is, the worse the vibes which will be generated.

Toh Han Shih is a Singaporean writer in Hong Kong. The opinions expressed in this article are his own.