by Rob Lever

The staggering figure of more than three billion fake accounts blocked by Facebook over a six-month period highlights the challenges faced by social networks in curbing automated accounts, or bots, and other nefarious efforts to manipulate the platforms.

Here are four key questions on fake accounts:

How did so many fake accounts crop up?

Facebook said this week it “disabled” 1.2 billion fake accounts in the last three months of 2018 and 2.19 billion in the first quarter of 2019.

Most fake social media accounts are “bots,” created by automated programs to post certain kinds of information — a violation of Facebook’s terms of service and part of an effort to manipulate social conversations. Sophisticated actors can create millions of accounts using the same program.

Facebook said its artificial intelligence detects most of these efforts and disables the accounts before they can post on the platform. Still, it acknowledges that around five percent of the more than two billion active Facebook accounts are probably fake.

What’s the harm from fake accounts?

Fake accounts may be used to amplify the popularity or dislike of a person or movement, thus distorting users’ views of true public sentiment.

Bots played a disproportionate role in spreading misinformation on social media ahead of the 2016 US election, according to researchers. Malicious actors have been using these kinds of fake accounts to sow distrust and social division in many parts of the world, in some cases fomenting violence against groups or individuals.

Bots “don’t just manipulate the conversation, they build groups and bridge groups,” said Carnegie Mellon University computer scientist Kathleen Carley, who has researched social media bots.

“They can make people in one group believe they think the same thing as people in another group, and in doing so they build echo chambers.”

Facebook says its artificial intelligence tools can identify and block fake accounts as they are being created — and thus before they can post misinformation.

“These systems use a combination of signals such as patterns of using suspicious email addresses, suspicious actions, or other signals previously associated with other fake accounts we’ve removed,” said Facebook analytics vice president Alex Schultz in a blog post.

Does Facebook have the control of the situation?

The figures from Facebook’s transparency report suggests Facebook is acting aggressively on fake accounts, said Onur Varol, a postdoctoral researcher at the Center for Complex Network Research at Northeastern University.

“Three billion is a big number — it shows they don’t want to miss any fake accounts. But they are willing to take a risk” of disabling some legitimate accounts, Varol said.

Legitimate users may be inconvenienced, but can generally get their accounts reinstated, the researcher noted.

“My feeling is that Facebook is making serious efforts” to combat fake accounts, he added.

But new bots are becoming more sophisticated and harder to detect, because they can use language nearly as well as humans, according to Carley.

“Facebook may have solved yesterday’s battle but the nature of these things is changing so rapidly they may not be getting the new ones,” she said.

Varol agreed, noting that “there are bots that understand natural language and can respond to people, and that’s why it’s important to keep research going.”

Should I worry about bots and fake accounts?

Many users can’t tell the difference between a real and fake account, researchers say. Facebook and Twitter have been stepping up efforts to identify and weed out bogus accounts, and some public tools like Botometer developed by Varol and other researchers can help determine the likelihood of fake Twitter accounts and followers.

“If you use Facebook to communicate with family and friends you should not worry much,” said Filippo Menczer, a computer scientist who researches social media at Indiana University.

“If you use it to access news and share that with friends, you should be careful.”

Menczer said many Facebook users pay little attention to the source of material and may end up sharing false or misleading information.

“Everyone thinks they cannot be manipulated but we are all vulnerable,” he said.

Along with bots, humans represent a key element in the misinformation chain, researchers say.

“Most false information is not coming from bots,” Carley said. “Most of it comes from blogs and the bots rebroadcast it” to amplify the misinformation.

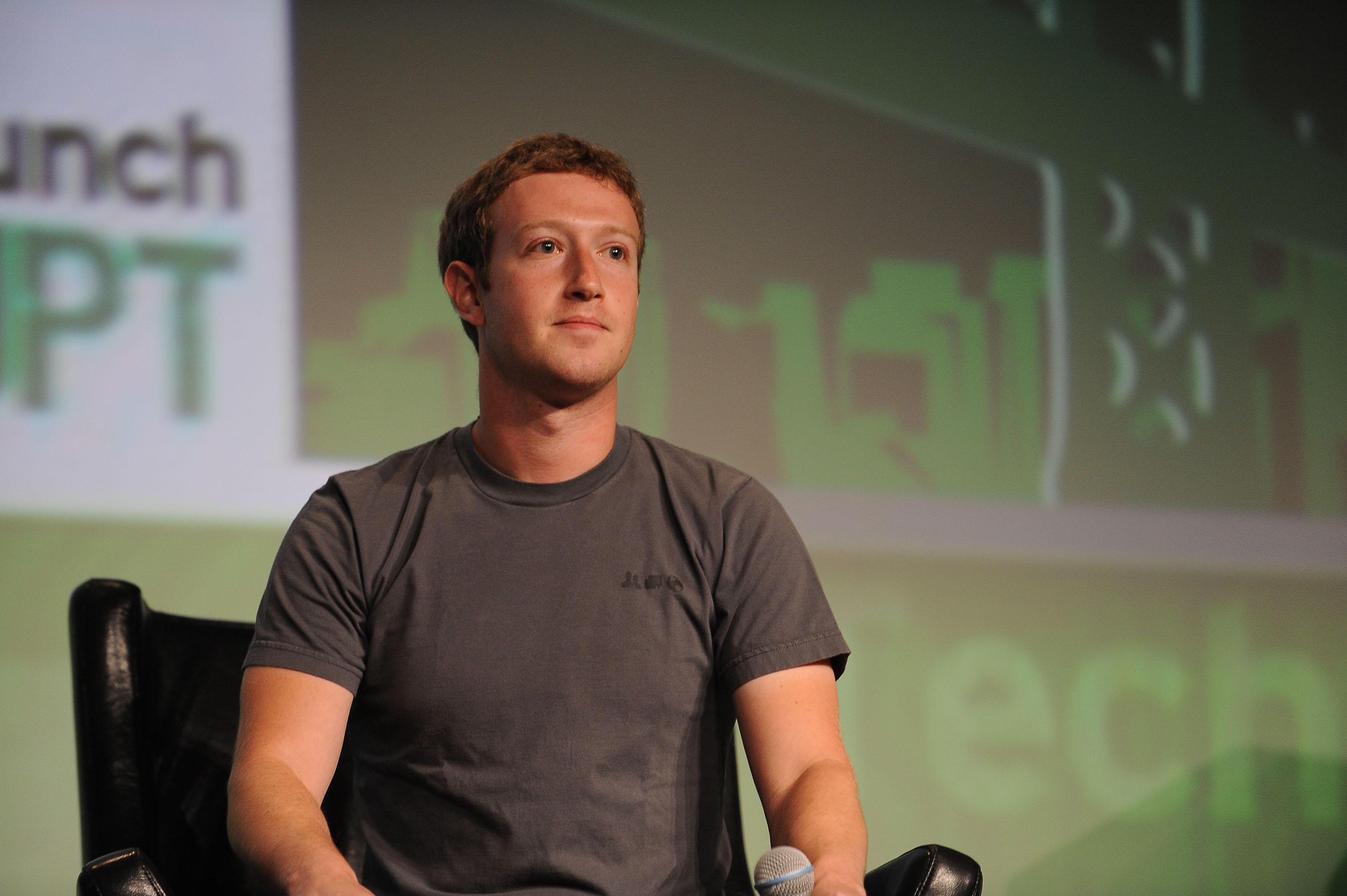

Facebook chief Mark Zuckerberg said Facebook is seeking to eliminate the financial incentives of fake accounts.

“A lot of the harmful content we see, including misinformation, are in fact commercially motivated,” Zuckerberg told reporters. “So one of the best tactics is removing incentives to create fake accounts upstream, which limits content made downstream.”

rl/jm

© Agence France-Presse

/AFP