By Augustine Low

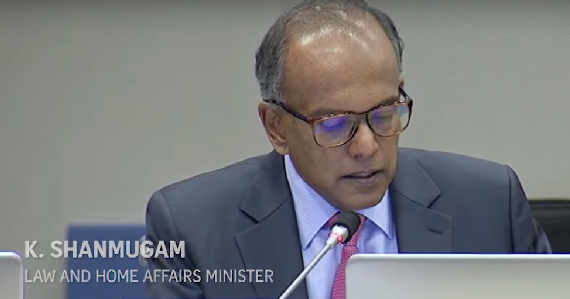

To say that K Shanmugam wields far-reaching influence is an understatement. He is a mover and shaker who pulls the strings, calls the shots and makes things happen.

Shanmugam is conduit, conductor, mastermind, knuckle duster and sledgehammer all rolled in one. Has there ever been a cabinet Minister as powerful as him?

He in the thick of the taking down of anyone deemed to have gotten out of line, whether from within or outside the establishment. He is quick to rattle the Opposition whenever it dares to make any incursions or insinuations.

Pro-establishment figures who let down their guard momentarily and veer away from the script get the short end of the stick from him. Just ask Kishore Mabubani and Donald Low from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy. Both were publicly and unceremoniously rebuked last year for remarks seen as unbecoming. Donald apologised profusely not once but several times and has stayed on. Kishore retired as Dean of the school, after leading it since its founding in 2004.

Shanmugam holds the fort at two key ministries – Home Affairs and Law. He has reshaped both portfolios in his own image, overseeing key appointments and expanding scope and breadth.

So pervasive is his influence that you just cannot imagine something as momentous as the Reserved Elected Presidency coming to pass without his orchestration. It might be said that he is both brainchild and executor of such happenings.

The unique role that Shanmugam plays – with consummate skill and ruthless efficiency – can be seen in the setting-up of the Select Committee on Deliberate Online Falsehoods. The government had long wanted to rein in social media, which it considers an untamed beast that is messy, unhinged and disruptive. Is there anyone better equipped than Shanmugam as the driving force, propelling the government to get on top of policing cyberspace?

On the final day of the Select Committee hearing, Shanmugam grilled historian and PAP critic Thum Ping Tjin over the interpretation of historical events such as Operation Coldstore and the Hock Lee Bus riots. Shanmugam was out to discredit Thum, who had accused the PAP of using fake news to detain political opponents. The Minister was determined to poke holes, the most glaring one being that Thum did not cite the first-hand accounts of former Community Party of Malaya leaders such as Chin Peng in his research paper. Thum stood his ground but the protracted back and forth led to the historian eventually conceding that parts of his paper could have been worded better.

Beyond who won or lost the marathon exchange, the key takeaway is that Shanmugam is hell bent on getting his way and getting on top – against anyone. He had the remarkable resolve, stamina and discipline to grill Thum for almost six hours. He took the trouble of getting thoroughly acquainted with Thum’s research paper so that he could seize on any flaws.

Surprisingly, though, in a past interview, Shanmugam told The Straits Times that he did not read the book by law academic and former wife Jothie Rajah – Authoritarian Rule of Law – which argues forcefully that the rule of law is a subjugating rather than a liberalising force in Singapore. The Minister not only picks his fights, he also picks what he wants to talk about.

Although most people’s perception of Shanmugam is that of a hard man who gives no quarters, there is a softer, compassionate side to him. He has a few pet dogs and has said that the way we treat animals says something about us as humans. He has advocated for animal welfare groups such as Save Our Street Dogs and initiated a pilot project to relook the age-old policy of cats being banned in HDB flats.

The Minister has also held meetings with gay rights’ groups to get their feedback and representation as part of his community engagement efforts. He has said that when approached by any group on any issue, “I try and meet them to discuss.” With his constituents, encouraging parenthood is a pet cause. “Every time I see a kid, I’ll ask the parents, ‘So what can we do for you to consider having a second or a third?’”

According to his second wife Seetha, a clinical psychologist, Shanmugam is “shy and introverted.” And even in the midst of testy exchanges with critics and opponents, he manages to wear a smile.

Nevertheless, the hard, redoubtable, even fearsome side of Shanmugam is the one that shines through. In him, Lee Kuan Yew quite possibly saw a kindred spirit. It was Lee who by all accounts roped him into politics and later turned to him for legal counsel. Shanmugam was also an adviser to Lee and his family on matters relating to 38 Oxley Road and Lee’s final wishes.

The Minister is not one to give in to raw emotion, but on the passing of Lee, he wrote: “Each time I think about him now, I tear. Each time I read a tribute to him, I choke. It is difficult to describe in words, the grief I feel.”

There is a shared affinity with how both men go about their political roles and life’s mission. Shanmugam described Lee Kuan Yew as a “practical, no-nonsense man . . . his sharp intellect meant getting straight to the heart of any issue. There was no small talk or superficiality.”

This is strikingly similar to how Shanmugam describes himself: “People know I mean what I say . . . I don’t sugarcoat or say something people like to hear. I prefer to be honest and direct. I think there is value to that.”

Like Lee, Shanmugam brooks no nonsense, no dissent. He does not mince words, preferring to see things in black and white and to cut to the chase. If there is any semblance of a threat, he would move to nullify it.

Shades of the student emulating the master? If so, taking the leaf out of Lee Kuan Yew’s book has served Shanmugam very well indeed. Today the power and influence he wields eclipses that of any other Minister.