by Sean Lim

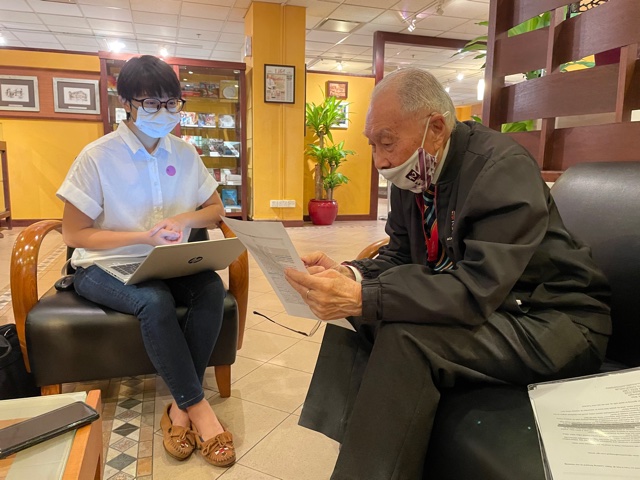

Much has been said about the accomplishments of pioneer civil servants featured in The Last Fools: The Eight Immortals Of Lee Kuan Yew, a book written by Peh Shing Huei and seven other journalists from content agency The Nutgraf.

There was Andrew Chew, who helped to map out Singapore’s ambulance service. George Bogaars, for example, was instrumental in setting up the Singapore Armed Forces Training Institute.

Peh, the book’s editor, was most impressed by the cleanup of the Singapore River because it laid the foundation for our water policies after that. He has Lee Ek Tieng to thank as the person behind the massive river cleanup and NEWater.

What struck me, however, was not so much about their achievements in the civil service. Instead, it was their strong personalities and attitudes which caught my attention. For one, they had no qualms challenging the status quo and speaking their minds.

Case studies from the book

And it’s not just Ngiam Tong Dow, a classic example whenever we mention the subject of ex-civil servants turning rogue. Of the eight, he made the most scathing criticisms of the government and civil service after his retirement.

In a 2013 interview, Ngiam criticised the civil service for becoming tamer and thus not ideal because a contest of ideas is needed within. His strong objection against high ministerial salaries is also now a go-to quote used by those arguing the same online.

I knew about Ngiam. His criticisms made headlines when I was studying in junior college and was mature enough to understand what was happening around me. I also knew Ngiam’s comments received a tersely-worded response from the Prime Minister.

But there were others, too, who did not shy away from making pointed comments publicly when dissatisfied with the Establishment, even when they were still in the civil service.

When I assisted veteran journalist Bertha Henson with researching Not For Circulation: The George E. Bogaars Story, I found out how Mr Bogaars chided the civil service for being “terribly overstaffed” in his capacity as the civil service’s top honcho. In the same capacity, he also complained about how the civil service didn’t pay their employees enough compared to those in the private sector.

In Peh’s book, it was written: “All were unflinching when speaking to their political masters, as they were not afraid to ‘tell the bosses off’”. The book also cited Lee Ek Tieng, who lamented the younger leadership in government:

After juggling multiple portfolios at the height of his career, Lee developed great respect for the older ministers, who were more interested in the big picture and would leave the day-to-day running of the ministry to the permanent secretaries. In his interview with the Oral History Centre, he said the younger generation of ministers are technocrats who want to know every detail. “I wouldn’t say they are not good, but it is a question of where you have to draw the line,” he said.

In those days, they were equals

As a young Singaporean who grew up associating the civil service with subservience, reading about personalities who were otherwise was unexpected. I asked the book’s author: how could these pioneer civil servants have done that?

“Perhaps it is inevitable for them to have very strong views of the civil service. After all, they were pretty much the same people who built up the civil service,” Peh said. “In a way, their criticisms are justified. But their criticisms must also be contextualised.”

He elaborated that in those days, these civil servants saw themselves on par with the political leaders rather than as subordinates. After all, they belonged to the same generation as Lee Kuan Yew, Goh Keng Swee, and the other founding fathers.

“They were peers. While these eight bureaucrats were expected to execute ideas, in the eyes of the political leaders, they were equal with each other in life and in wits. So they were just as capable and just as smart. Because of that, I think there is very strong and mutual respect going on, that they will allow that kind of open talk,” Peh said.

As such, I conclude that these civil servants don’t view the Old Guard with the same awe as we do today. Perhaps their relatively-lower salary is a factor. Peh didn’t bring this up in the book, but in Henson’s biography on Bogaars, she stated that when the former permanent secretary retired in 1981, he was earning about $6,000 monthly, equivalent to about $11,000 today. As a result, less was at stake for them financially and thus less cautious about speaking up.

In contrast, a permanent secretary today may well earn at least $59,760 a month, a pay grade matching that of an entry-level minister if figures from 2008 did not change significantly. Unfortunately, the salary data of top civil servants in recent years is not publicly available.

But Peh reminded me that while these civil servants had strong minds of their own and were unafraid to speak their minds, they were also aware of the optics. “They were not going to stand up there and contradict Lee Kuan Yew or Goh Keng Swee. I don’t think they did,” he said. This could have explained why most of them expressed their views only years after retirement.

A different civil service (and Singapore) then

Also, Peh said that the civil service of the 1960s and 70s differed.

How different? Peh described the civil service then as a body in its infancy with less red tape. “The layers were flat,” in his words. With the extra urgency to get things done in a developing Singapore, those civil servants had significant autonomy to do their work.

This same group also couldn’t care less about official procedures and, at times, nearly got themselves into trouble. For example, there was a story in the book where Andrew Chew, while in the Health Ministry, went ahead with his nationwide ambulance service project without submitting the necessary Cabinet papers.

“The ministers at the top had no idea what was going on, which could have posed issues for those dealing with the grassroots,” the book wrote.

As rules on speaking up publicly bind civil servants, such as the Official Secrets Act, they are usually tight-lipped about the inner working culture, especially today when there aren’t any tell-alls by current senior civil servants.

At best, anecdotes exist in the private sphere or meme accounts parodying the Foreign Affairs Ministry, Home Affairs Ministry, or government ministries in general. While done informally, these tales reveal a highly-bureaucratic culture within the service and, at times, reflect the very imperfections criticised by these pioneer civil servants.

That said, Peh reminded readers “to be aware that to compare it (yesterday’s civil service) to today’s civil service is really not very fair. We are talking about two completely different entities in many ways.”

“Compare it to today, when we are a developed nation, you can’t expect today’s civil servants and permanent secretaries to behave like them. It’s just impossible. It’s like expecting you to behave like your grandfather,” Peh said.

“I would think that it is still very much talking about a civil service with completely different challenges from the ones they faced. Because of that, it requires a completely different mindset and a completely different way of doing things.”

Another explanation of why we tend to romanticise the pioneers: Many things are done today but on the foundations, they have built. The achievements of these pioneers look significant because there was no precedence. Therefore, following up on them is usually perceived as less consequential than the first step taken.

Take Changi Airport, for example, which Sim Kee Boon built. “Terminal five is being built after terminals one, two, three, and four. Doesn’t sound as exciting as a brand new airport, right?” Peh told me.

“Whatever being done today in the context of that when you are building a brand new airport, it is much more difficult but more exciting. This is not to say that terminal five is not exciting—it is also going to be enormous—but it is not the same.”

What has worked, could still work, and could no longer work?

Singapore has evolved tremendously from the 1960s, so what can we learn about yesterday’s civil servants that can and can’t work today?

For sure, they cannot bulldoze policies the same way Howe Yoon Chong did during his time. Howe was the “immortal” who left the deepest impression on Peh, not surprising since he was the writer for that chapter. Peh was also the Straits Times journalist who reported on Howe’s passing in 2007.

Howe, who helmed the civil service from 1975 to 1979, later entered politics and became a minister for the defence and health ministries.

Peh told me that Howe, whom he admired as someone with great foresight, was known as a bulldozer because he would execute policies based on guts and instincts. Howe was a civil servant with the conviction and confidence to know what he did was right, even if naysayers cast doubts on him.

According to Peh, history had proven that Howe was right on many occasions, such as his decision to reclaim land to create Marine Parade, long before Malaysia and Indonesia started paying attention to Singapore’s reclamation.

“This is a guy who bulldozes through things—meaning that he didn’t really care for feasibility studies or five-year plan or whatever,” Peh said.

Could it still work today?

But today, consultation has become de rigeur of public life. So to continue with Howe’s approach would have been unwise and even thrown DPM Lawrence Wong’s Forward Singapore movement into disarray, given that the exercise is for the government to build a consensus with Singaporeans.

“I don’t think Singaporeans today appreciate it if you just go there and do anything you want. They want to be consulted, like: ‘Let’s take this discussion out of the civil service and bring this to the people. Singaporeans prefer to slow things down and have someone say, “Hey, wait a minute, are you sure you want to do that?” Peh said.

“If we have a Howe Yoon Chong today that says: ‘I don’t care, I’m just going to drive a road through, damn with your cemetery’, citizens are going to be very angry,” he added, using the Bukit Brown controversy as an example if there hadn’t been any public consultations at all.

An uproar over the Howe Yoon Chong Report in 1984 proved this point, even as far back as 38 years ago. In that report looking into the problems of an ageing population, Howe and his team proposed to raise the Central Provident Fund withdrawal age from 55 to 60, then to 65.

There was widespread unhappiness, and the government shelved the proposal. But as Peh wrote, the damage was done and at the polls held the same year, the People’s Action Party suffered a 12 per cent drop in their share of votes. The ruling party also lost Potong Pasir to the Opposition, on top of J.B. Jeyaretnam holding onto his Anson seat.

Sure, Howe’s solution from the report has “stood the test of good time and sense”, as Peh wrote. Today, a Singaporean worker can withdraw his CPF savings at 55 but must maintain a minimum sum, which is $96,000 today.

But this controversy showed that the most well-intended policies could go awry if not appropriately communicated and bulldozed through. Philip Yeo, an ex-civil servant, was quoted in the book saying: “The problem was not the report. The problem was the marketing of the report. Howe Yoon Chong was very blunt.”

This approach didn’t succeed in 1984 and certainly wouldn’t in 2022. While Peh said that bulldozing may not work today, he told me that pioneer civil servants like Howe’s gung-ho and “can-do” spirit are still worth emulating. However, given the complexities of the world today, Peh admitted that upholding these values is more challenging than before.

I wonder how a similar book like this, which Peh described as a “little passion project”, will look 20, 30 years later. I cheekily asked him this hypothetical question in an attempt to get him to judge today’s civil service.

“Unlike Howe Yoon Chong, I can’t predict. I’m only good at looking back,” he said.

The Last Fools: The Eight Immortals of Lee Kuan Yew (edited by Peh Shing Huei) is published by The Nutgraf Books. Besides Peh, contributors are Sue-Ann Chia, Jacqueline Woo, Justin Kor, Samantha Boh, Prabhu Silvam, Aaron Low and Derek Wong. The book is available here for S$24.00.

Sean Lim is a former journalist at Rice Media, and he used to report on socio-political issues and current affairs