By Jeannette Chong-Aruldoss

27 June 2022

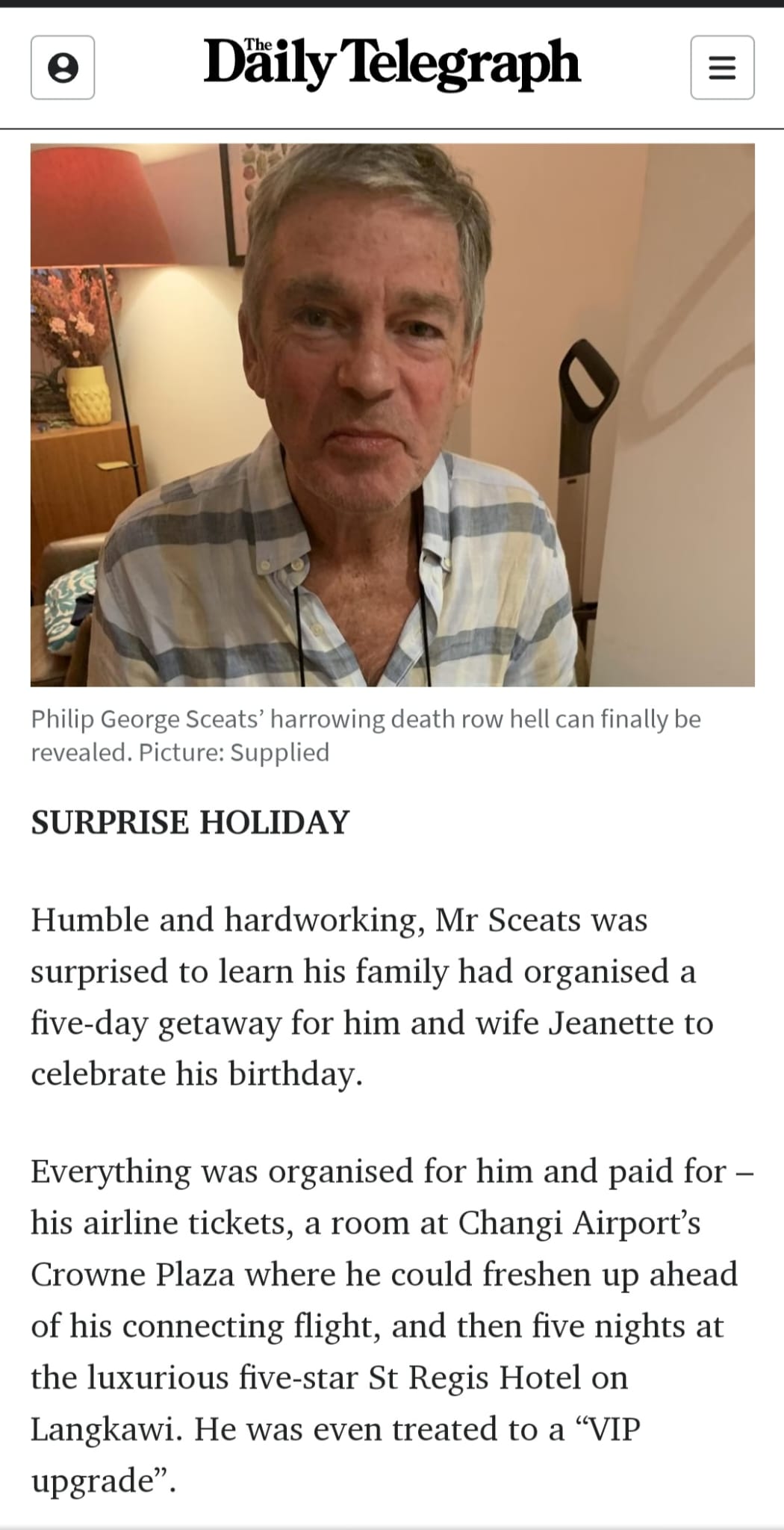

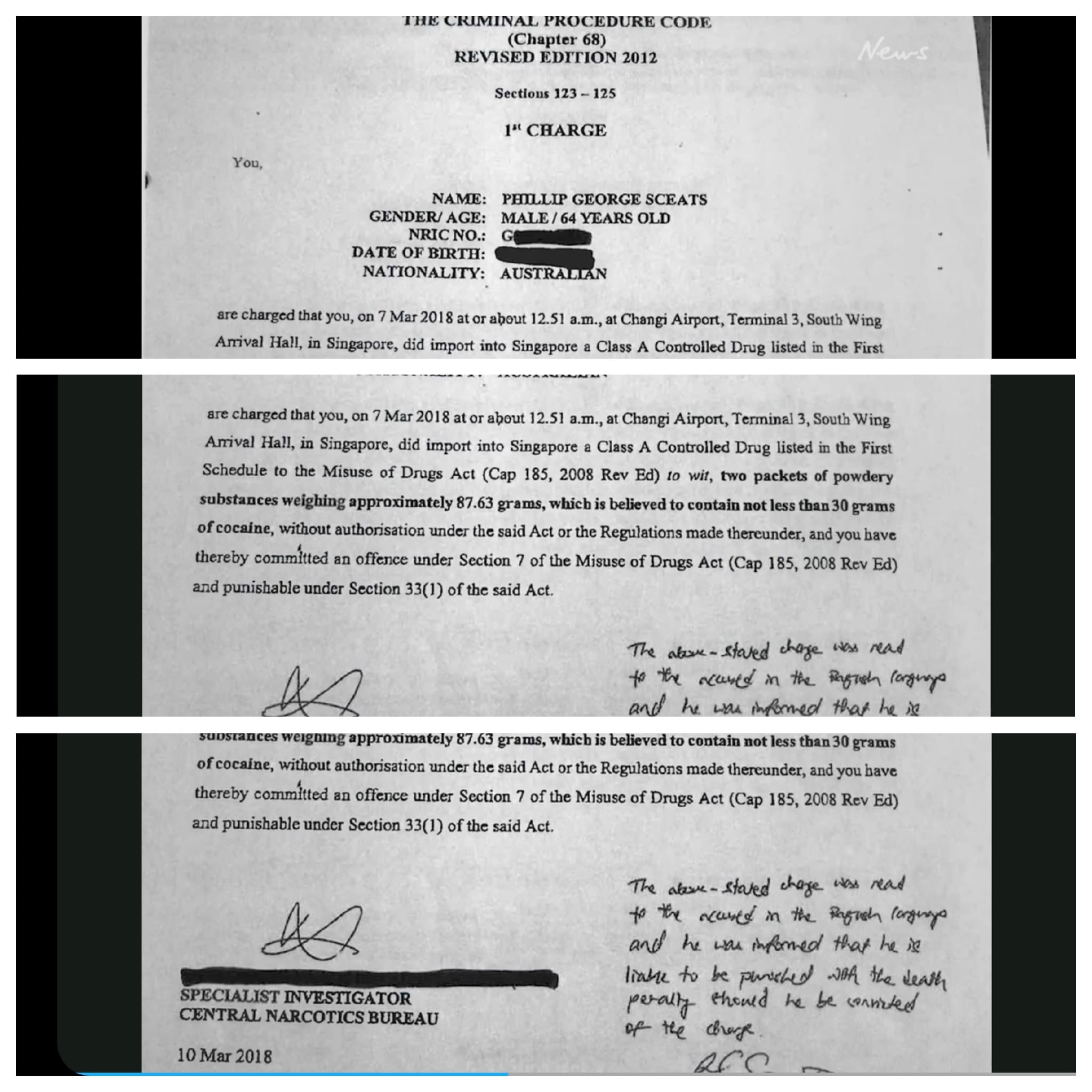

I bet you didn’t know that in 2018, an innocent Australian holiday-maker was arrested at Changi Airport and charged with trafficking an amount of cocaine punishable by death. 64-year-old Sydney businessman, Philip George Sceats languished in Changi Prison for the next 353 days, under the pall of the capital charge.

Then one day, as unexpectedly as he had been arrested, he was taken from his cell to court where he was discharged of the capital charge and told to leave Singapore within 24 hours. Sceats’ arrest in Singapore on 7 March 2018 and his release from prison on 23 February 2019 was never reported by any media at the time.

It was only revealed when his story was picked up by Australian journalist Natalie O’Brien and published by News Corp Australia on 18 October 2020.

O’Brien wrote that Sceats’ wealthy Sydney family had booked a holiday in Langkawi for him and his wife, to celebrate his 64th birthday. Sceats was to fly from Sydney to Singapore, where he would wait for six hours to catch his connecting flight to Langkawi. His wife, who was in Hong Kong for business, would meet him in Langkawi. His family also booked him an airport hotel room for him to rest before his flight to Langkawi.

In the early hours of 7 March 2018, Sceats arrived at Changi Airport. Just as his passport was stamped by Singapore immigration, he heard police officers calling out his name. The police officers then escorted him to the luggage carousel to pick out his suitcase.

When his suitcase was opened in their presence, two packets of white powdery substance secured by masking tape were found inside the suitcase.

Sceats had no idea how those packets got into his suitcase. The shocked and bewildered Australian was immediately handcuffed and conveyed to Changi Prison.

Meanwhile, the Singapore police had the two packets of white powder, which weighed about 90 grams in total, lab-tested. They were found to contain 39.4 grams of cocaine.

Under Singapore law, anyone found in possession of more than three grammes of cocaine is presumed to have had that drug in possession for the purpose of trafficking unless it is proved that his or her possession of that drug was not for that purpose.

The penalty for trafficking more than 30 grammes of cocaine is death.

On 10 March 2018, the third day of his incarceration at Changi Prison, Sceats was formally charged with the capital charge of trafficking 39.4 grams of cocaine.

Facing the spectre of the hangman’s noose, Sceats’ plight could not be more dire. Fortunately for him, his family had the means, influence, and determination to save his life. They engaged a well-known Singapore criminal lawyer to defend him against the capital charge. They also hired a team of high-credentialed private investigators and consultants to find evidence that would convince the Singapore authorities that he was innocent of the charge and that he had been set up by persons unknown. Sceats’ high-powered team included former high-ranking police officers from three different Australian states.

The team took stock of the many things in Sceats’ case that did not add up.

According to O’Brien, the street value in Sydney for the amount of cocaine found in Sceats’ suitcase was AUD $27,000 to AUD $30,000, but it was worth less than half of that in Singapore and Malaysia. There was no money to be made from smuggling cocaine from Australia to Singapore, so it was bizarre for anyone to attempt to do so.

Also, Sceats was not searched before he boarded his flight to Sydney. But by the time he arrived at Changi Airport, Singapore police officers were waiting for him. They knew his name and his arrival details. This meant that the Singaporean authorities had been tipped-off by someone after Sceats’ flight left Sydney and before it arrived in Singapore.

After working on Sceats’ case for several months, his team of private investigators produced a thick file of evidence and documents. Sceats’ Singapore lawyer furnished the dossier to the Attorney-General Chambers, urging that his client was nothing more than an innocent holiday-maker who had been set-up.

On 23 February 2019, not knowing what to expect, Sceats was brought to Court. That day, a judge granted him a Discharge Not Amounting to an Acquittal. Freed at last from his ordeal, Sceats returned to Australia.

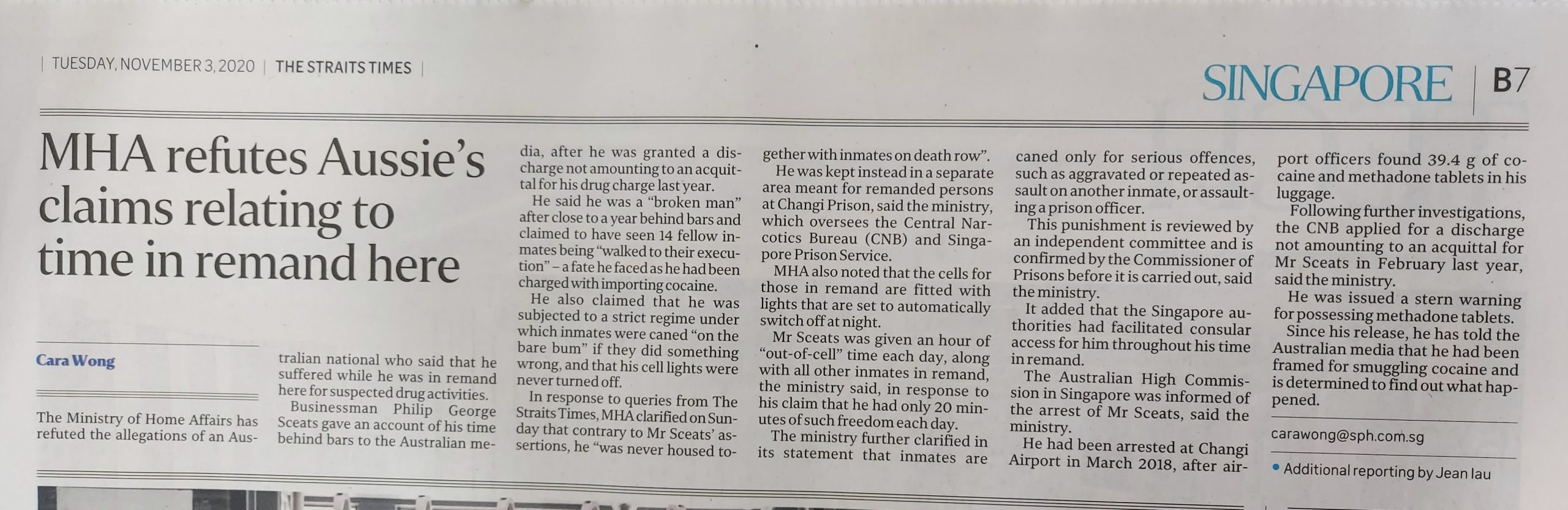

While telling Sceats’ story, O’Brien’s article also related Sceats’ experience as a prisoner in Changi Prison. However, Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) had things to say about Sceats’ account of his time at Changi Prison. It was MHA’s beef with Sceats’ depiction of local prison conditions that finally earned him a spot in The Straits Times.

On 3 November 2020, Straits Times published an article “MHA refutes Aussie’s claims relating to time in remand here” which gave MHA’s rebuttals to Sceats’ account. O’Brien’s article had stated:

1. Sceats was held on death row.

MHA clarified that Sceats “was never housed together with inmates on death row” but in a separate area meant for remanded persons at Changi Prison.

2. Sceats said: “We were allowed out for 20 minutes at a time.”

MHA clarified that Sceats was given an hour of “out-of-cell” time, along with all other inmates in remand.

3. Sceats said “Guards come past your cell every hour. They don’t turn the lights out when you are on the death penalty.”

MHA clarified that the cells for those in remand are fitted with lights that are scheduled to automatically switch off at night.

4. Sceats said “It was very strict regime in there. If you do something wrong they give you the cane on the bare bum. They say it is like sitting on a barbecue.”

MHA clarified that inmates are only caned for serious offences, such as aggravated or repeated assault on another inmate or assaulting a prison officer. This punishment is reviewed by an independent committee and is confirmed by the Commissioner of Prisons before it is carried out.

5. Sceats said “I think 14 guys were executed while I was there.”

Of all the details that Sceats had told O’Brien about his time at Changi Prison, this was the most chilling.

But MHA gave no rebuttal to that claim.

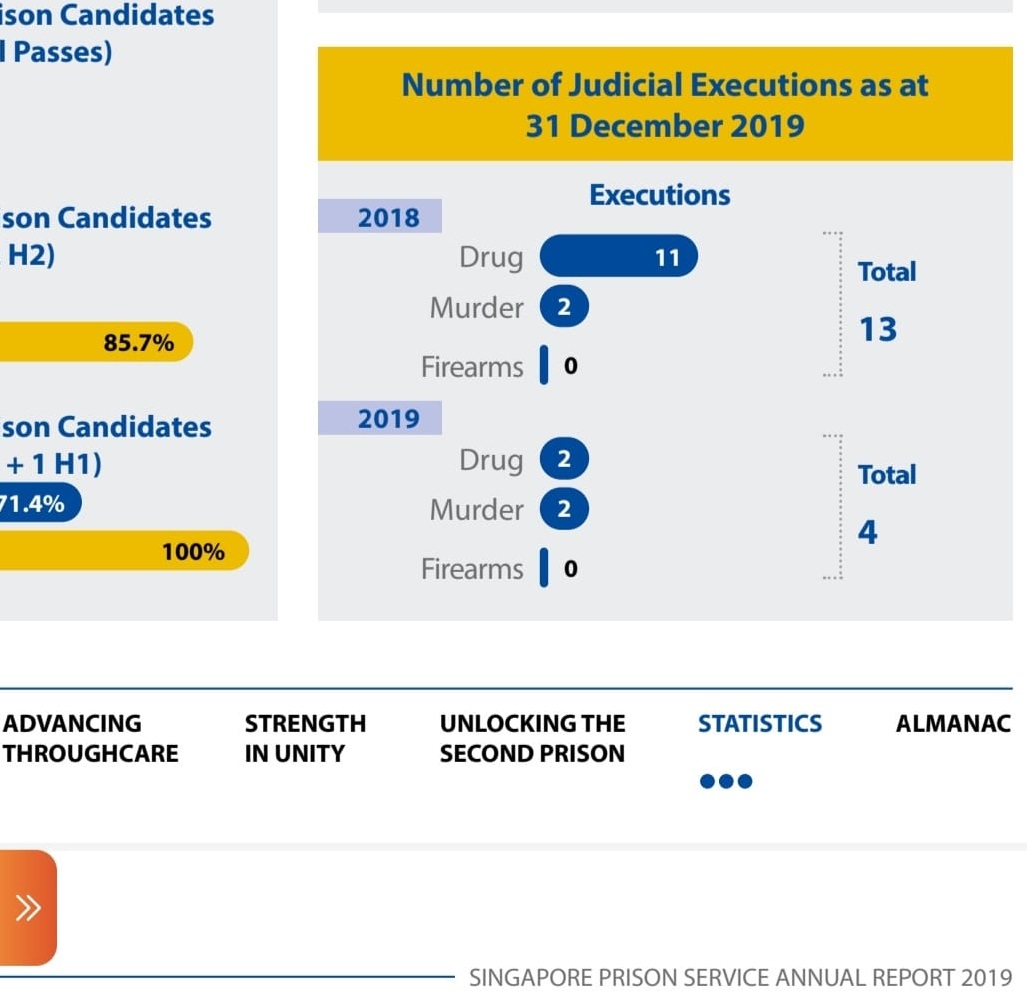

Was Sceats exaggerating? Sceats was in prison from 7 March 2018 to 23 February 2019. I looked up the 2018 and 2019 Annual Reports published by Singapore Prison Service. In 2018, there were 13 judicial executions. In 2019, there were 4 judicial executions.

Sceats was about right when he said he reckoned 14 hangings were carried out during his time at Changi Prison. No wonder, MHA said nothing about that.

While our national broadsheet’s coverage of Sceats’ story centred on explaining MHA’s rebuttals, Sceats’ story is not about prison conditions in Singapore.

Sceats’ story is a cautionary tale of a holiday-maker who was arrested on arrival in Singapore and imprisoned for almost a year at Changi Prison on a capital charge; and how it took almost a year, during which strenuous efforts were made on his behalf, before his nightmare in Singapore ended.

Singapore may have closed its file on Sceats, but there is no closure for Sceats.

How did the Singapore Police come to know Sceats’ name and arrival details?

Who told Singapore Police Sceats’ name and arrival details?

Sceats’ team wrote to both the Singapore and Australian authorities to find out, but no satisfactory answers have been obtained.

“I would give anything to know what really happened,” Sceats had told O’Brien.

As for the rest of us, Sceats’ case raises several troubling questions.

Was the dossier prepared by Sceats’ team of private investigators instrumental in securing his freedom?

Could the Spore authorities have, on their own accord, eventually arrived at the conclusion that they had caught and imprisoned an innocent man?

If Sceats did not have the means and resources to obtain the best available expert help, would he have made it to freedom?

Villains had opened his suitcase, planted the contraband substance inside it, contacted the Singapore police and provided them with Sceats’ name and arrival details. Could what happened to Sceats, happen to anyone?

Perhaps Sceats’ profile and circumstances as a 64-year-old wealthy Australian businessman worked to make him an unlikely cocaine smuggler.

If the next unlucky person to be framed by villains is one without means or favourable profile – what would be his chances of escaping the hangman’s noose?

Indeed, Sceats’ case is very curious, and also disturbing.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of The Independent Singapore.