By PN BALJI

Editor, The Independent Singapore

The city-state of Singapore appears to have run squarely into a mid-life crisis nine years after Lee Hsien Loong became prime minister, and two years after an embarrassing general election outing by his ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) and 18 months after a humiliating by-election defeat. The question observers in some circles have begun to ask is this: Just exactly where is Singapore’s leader?

In a country where leadership has traditionally been decisive, clear and in your face, the government under Lee in recent years has been uncharacteristically muddling through a mini-crisis of confidence. There have been complaints from Singaporeans about the seemingly unchecked entry of foreign workers into the country, the growing rich-poor divide, the high cost of public housing, an overworked public transit system that has been plagued by delays and breakdowns, and scandals involving top civil servants.

Even the one thing that Singapore has had bragging rights over in the past – its high annual economic growth rate – is now fading as the country becomes a mature economy and settles into more modest growth rates. The mood of the nation is turning sour, with the population “wanting to have the cake and eat it, too”, as Eugene Tan, an assistant law professor at the Singapore Management University (SMU), said.

Former Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong recently described the malaise as that of a nation reaching a mid-life crisis and hitting an inflexion point. Singapore is beginning to look like a listless and rudderless boat in an ocean of uncertainty.

For the first time…

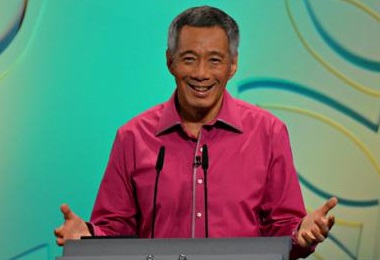

But then came Sunday, August 18. Prime Minister Lee addressed the nation for the 10th time on the occasion of the country’s most important speech of the year, that marking independence day.

This time, the prime minister came out fighting, with a speech that even observers such as Singaporean academic Cherian George referred to as “probably Lee Hsien Loong’s best National Day Rally speech.”

The nation saw Lee for the first time imprinting his own style on the annual address, saying that the country was at a turning point and the government was making strategic shifts to position Singapore for the next chapter in its future.

For the first time in a long while, Singaporeans saw a prime minister showing empathy for the masses, referring to the need for appropriate social policies and betraying a slight left-of-centre shift in political ideology. It looked as though the government was going back to its socialist roots during the early days leading to independence.

There were references in the speech to grants for young citizens to buy public housing, measures to ease the anxiety of parents about getting their children into schools of their choice and, most important, a decisive move to bring every Singaporean under a comprehensive medical insurance scheme.

Don’t worry, Lee said emphatically, we will take care of you. In a measure of how sweeping Lee’s speech is being perceived, opposition politician Gerald Giam said, “The speech was a recognition that major reforms, and not just incremental tweaks to policies and philosophies, are necessary.”

To be sure, not everyone was convinced that the shift by Lee was genuine. Donald Low, associate dean of executive education and research at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, said the government is not on a reformist path. “I would argue that the changes reflect a government that continues to believe in the currency and relevance of its long-established script – but also one which is prepared to deliver its lines and perform its role differently,” he said in a commentary.

Former prime minister Goh said his successor is having a tougher time than his predecessors. Lee is still trying to find his feet governing a country buffeted by an unsettled population and a mature economy.

SMU’s Tan added, ” It’s hard to, and probably not fair, to compare…(but) a case can be made that Lee Hsien Loong has a tougher job because success is now harder to come by and society a lot more complex and diverse.

He has to look after material concerns and post-material aspirations unlike his two predecessors, who very much had to worry about material concerns.

So, to garner the people’s strong support for government policies is a lot tougher today since more Singaporeans than ever before know only of a First World Singapore. The Third Word to First World grand narrative is losing traction with Singaporeans born after independence.”

The three PMs

There is another unseen and unspoken issue. After nine years as prime minister, it is difficult to pin down Lee’s defining attributes and distinctive style, his persona.

Singapore’s founder and first prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, took a nation, through crude and brutal domestic politics, to a level that nobody had ever dreamed possible. His successor, Goh, after a fitful early start, went on to stamp his mark as a consensus-building leader and rode a wave of strong economic growth.

But Lee Hsien Loong? He has served for nine years simply as someone who is known yet unknown.

Could it be that he came into office ever conscious of being his father’s son? He was always going to be compared to his father. That was inevitable. But it was unfortunate, because his father’s substance and style are now out of fashion.

George W. Bush, in his memoir, Decision Points, pointedly said, “the truth is that I never had to search for a role model – I was the son of George Bush (Sr.).”

There is a parallel here in Singapore. Lee Hsien Loong’s role model was inevitably seen to be that of his father. As the first-born son of his father (as George Bush Jr. was of Bush Sr.), Lee had an unspoken duty to follow in his father’s footsteps.

When decisive actions have been needed during his tenure as prime minister, he must have asked himself: Will I be seen as my father’s son? And will today’s generation accept that?

The Internet

Then, there is the Internet. Lee and his team have still not come to understand and embrace this wild, wild world of opinions. A nation constrained by a government that has traditionally communicated that it always knows what is best for the people has finally found its public voice.

And what would you expect of a public still in the first flush of a new-found freedom? They will grab the megaphone to make their voices heard, sometimes without a thought about the veracity and validity of their views.

They will test the waters to see how far they can go.

Perhaps this is the karma of Lee Hsien Loong’s government.

Quotations from the prime minister in a recent book co-authored by Google executive chairman Eric Schmidt show how far behind the curve the government is in coming to grips with politics in the digital world.

“The danger we face in future is that it will be far easier to be against something than for it,” Lee is quoted as saying.

By all accounts, the prime minister is highly respected for his intelligence. Those who have worked with him say that his ability to zero in on a problem, identify the underlying issues and come up with solutions is unquestionable.

But in today’s Singapore, more than that is needed. What is needed is someone who is prepared to cast aside past policies that are causing different people different problems, roll up his sleeves and move a nation.

As SMU’s Tan said: “There is a growing desire for more consultation before policy is made, for a less dominant PAP government in many facets of Singapore life, for more political pluralism and checks and balances.

Then, there is the challenge of Singaporeans wanting an effective and efficient government, while desiring a less assertive and less domineering government.

It’s a case of Singaporeans wanting to have their cake and eat it, too.

In short, PM Lee’s challenge is the need to remain popular in a more competitive political setting while eschewing populist policies that may generate short-term gains but imperil the long-term future of Singapore and Singaporeans.

The Cabinet

Lee also suffers from a cabinet that pales in comparison to the distinguished officials who populated the cabinets of the two previous prime ministers. Where today, for example, are the Goh Keng Swees, S. Rajaratnams, Lim Kim Sans, S. Dhanabalans, Tony Tans, Ong Teng Cheongs of previous generations?

Tan said: “Unlike his predecessors, who led Singapore with a group accustomed to the school of hard knocks, the lack of a political baptism among the 3G and 4G leadership means that PM Lee’s cabinet does not have the full complement of moral authority.

The long years of political dominance (1959 to date), including political hegemony between 1968 and 1981, have also meant that the PAP machinery is not as robust a fighting machine as it was in the 1960s to 1980s.

In short, the cruelest of cards has been dealt Singapore’s current prime minister. He has just another three years to reshuffle those cards before he faces his biggest electoral test. That test is not just for him, but for a country that is seen by many in Asia as a model for prosperity and harmony. It remains to be seen how he plays those cards. But his August 18 National Day speech suggests he may have a card or two up his sleeve.