Yesterday, the nurses’ rights group SG Nightingales made reference to a slogan used during the recent nurse strike in Australia.

The slogan – Stop Telling Us to Cope – is especially salient in Singapore’s context. As many nurses were at their wit’s end, the national broadsheet printed headlines that said: “hospitals were coping well“. These motherhood statements were called out by healthcare workers.

Leaving slogans aside, the question that we often wonder about is whether strikes actually work in Singapore?

Very often we are told, or taught, that workers’ strikes do not work in Singapore. However, the story of an aircraft engine manufacturing company might prove the contrary.

On 29 July 2020, the National Trade Union Congress (NTUC) and three unions said that they intervened the week before to stop unfair retrenchment practices by aircraft maintenance, repair, and overhaul firm Eagle Services Asia. ESA is a joint venture between SIA Engineering Company and American aerospace manufacturer Pratt & Whitney.

ESA had not followed the company’s due process for retrenchment and went ahead to inform some workers that they may be laid off even before talks with the aerospace and aviation unions concluded.

In response, Labour Chief and PAP CEC member Ng Chee Meng authorised unions to prepare for industrial action if management did not budge. A secret ballot among the workers was conducted, which received “overwhelming support”.

To let everyone understand that NTUC will stand up to protect our workers, I authorised our unions to prepare for industrial action should it become necessary to persuade management not to take unilateral decisions. We wanted a fair negotiation. The three unions conducted a secret ballot and workers gave overwhelming support to pursue legal industrial action.

Subsequently, the firm reversed its stance and went back to negotiate with the union. Based on public sources, the aim of the negotiations was to “ensure the Singaporean core of the workforce is kept intact and consider retrenchments as the last resort amid the uncertain economic outlook”.

The negotiations rendered some lukewarm results. The number of people retrenched did not change significantly (about 140), but more Singaporeans managed to keep their jobs (a 10% change). The workers who were retrenched were given (according to ST) a “fair compensation package” and an additional training grant.

Between the threat of industrial action, where workers could have gone on strike, which would have cost the company a significant loss in profitability – and negotiations, it was clear that the former proved more effective as a strategy.

Did the rank and file workers have a chance to debate and discuss what a fair outcome would be? And were they able to discuss going on strike if the company did not comply?

But fast-forward to 15th February 2022. One of ESA’s partners, Pratt & Whitney, announced that they will be hiring 250 workers in Singapore. This will bring the firm’s headcount back to pre-pandemic levels. It’s not clear how many of these workers would be shifted to ESA and if anyone who lost their job previously regained it.

However, the vice president of Pratt & Whitney said that former employees who had been laid off (a total of 400 in August 2020) are welcome to apply for the new positions if interested.

While there are market factors to consider in the recovery of the aerospace and aviation sectors, might it be possible that the threat of industrial action (possibly a strike) had an effect too? After all, the mere ability for a majority of workers to go on strike increases their collective bargaining power and, thus, leverage in matters concerning them.

Given the power of workers taking industrial action, why is this not done more often? NTUC is a state-controlled union, and this severely limits what it can do for workers’ livelihoods. From the ESA example, however, we can get a glimpse of what a more active NTUC could do for workers.

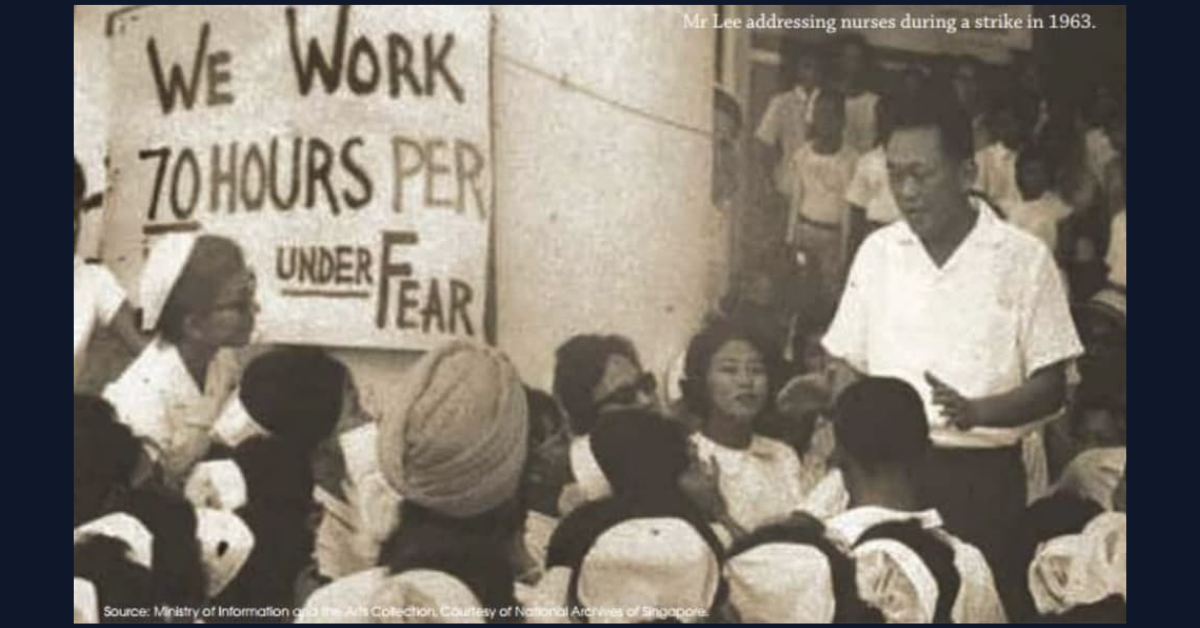

The last publicly-known strike authorised by the NTUC was in 1986 (by the late president Ong Teng Cheong). It is perhaps not a stretch to attribute labour’s significantly low share of national income compared to capital, to how tightly controlled and tame the NTUC has been.

Should it only be left to the labour chief, who has historically always also been a member of the ruling party, to authorise industrial actions? If the union is truly the workers’ then shouldn’t workers be the ones to decide when they wish to take industrial action?

In a time when 1 in 4 workers in Singapore are choosing to resign from their companies, wages do not seem to be increasing at the same rate as the cost of living, long working hours are preventing workers from spending much needed time with their families or even worse – causing them health problems, and healthcare workers may unable to even take their annual leave, perhaps a less controlled and therefore more independent and vibrant labour union is needed to ensure we have a genuine stake in our lives and future.

Since you have made it to the end of the article, follow Wake Up Singapore on Telegram!