SINGAPORE: As Singapore gears up for its most pivotal General Election in years, Ravi Philemon’s recent reflections on Marine Parade–Braddell Heights GRC and the broader state of opposition politics offer a sobering warning: if the opposition does not wake up, if it continues to fracture and falter, the only winner will be the People’s Action Party (PAP) — as history has repeatedly shown.

The Workers’ Party (WP)’s decision not to contest Marine Parade–Braddell Heights was surprising to many. However, as Mr Philemon noted, it is understandable when seen through the lens of pragmatism. He pointed out that the WP remains a relatively small party, despite its successes and mobilising resources — the much-needed “Vitamin Ms” of manpower, money, and media presence — demands tough decisions.

Still, while the WP’s calculus makes sense internally, the external reality for residents of Marine Parade–Braddell Heights is grim: there will be no alternative voice at the ballot box. In a country where democratic competition is already scarce, that is not a small loss. It could be a warning sign of a larger rot setting in within the opposition ecosystem.

The Historical Playbook: Fragmentation favours the PAP

Singapore’s history is clear. Whenever the opposition has been divided, distracted, or disorganised, the PAP has seized the advantage.

In 1997, opposition parties contested 36 seats against the PAP’s 83, and most battles were three-cornered fights. The result was a near wipeout. Only two opposition MPs were elected — Chiam See Tong and Low Thia Khiang. The PAP’s powerful electoral machinery, community outreach, and policy apparatus allowed it to deepen its hold, portraying the opposition as fractured and unreliable.

Every time the opposition frays into multiple camps, the PAP benefits — not through conspiracy, but through sheer structural advantage. It has the ground networks, the resources, and the ability to reassure an anxious electorate that “stability” and “unity” must trump all else.

And now, in 2025, we are seeing a repeat of this historical cycle. Other constituencies may yet see three-cornered or even four-cornered fights. And if that happens, we must be clear: the result will not be more choices for voters. It will be fewer opposition MPs, fewer checks and balances, and less real democracy.

Why so many opposition parties?

Some might ask: why can’t the opposition simply unite into one party? Why do we have so many opposition groups — WP, PSP, SDP, RDU, NSP, PPP, and others?

The answer lies in Singapore’s political reality. Each party represents different visions for the country and different strategies for change. Some, like the SDP, emphasise civil liberties and welfare reform. Others, like the PSP, focus on accountability and gradual reform from within. RDU seeks to represent the squeezed middle class and ordinary Singaporeans yearning for a fairer future.

These parties are born from real needs, real frustrations, and real communities. They are not vanity projects. They are genuine attempts to represent slices of Singaporean society that feel unheard or underserved by the status quo.

But in a mature democracy, multiple parties can coexist without sabotaging each other. The opposition’s challenge is not to erase their differences, but to mature past petty rivalries, to recognise that strategic cooperation must come before ego, ideology, or pride.

They must reach a stage where, even if they disagree on ideologies, they agree on the principle: Singapore deserves a strong, credible, united opposition.

PAP is here to stay. So is the opposition.

The PAP is not going anywhere, nor should it. It has an undeniable legacy in building Singapore’s success story. For all criticisms, it has steered the country to prosperity, peace, and global stature.

But prosperity breeds new challenges: rising inequality, declining social mobility, an ageing population, and the widening gulf between elites and ordinary citizens. No single party, however brilliant, has a monopoly on ideas or compassion. Singapore needs collaboration to stay vibrant, needs alternative voices to challenge assumptions, propose new policies, and hold those in power accountable.

The opposition is not here to “overthrow” Singapore. It is here to strengthen it.

Yet the opposition must also recognise: survival is not guaranteed. A total opposition wipeout in Parliament is possible. If the electorate perceives them as divided, untrustworthy, or chaotic, voters will swing decisively towards the familiar and the stable — the PAP.

This is why Mr Philemon’s message matters so deeply. The bonds of camaraderie that once linked opposition parties are fraying. The shared sense of purpose — that it is not about personal ambition, but about serving the people — is under threat.

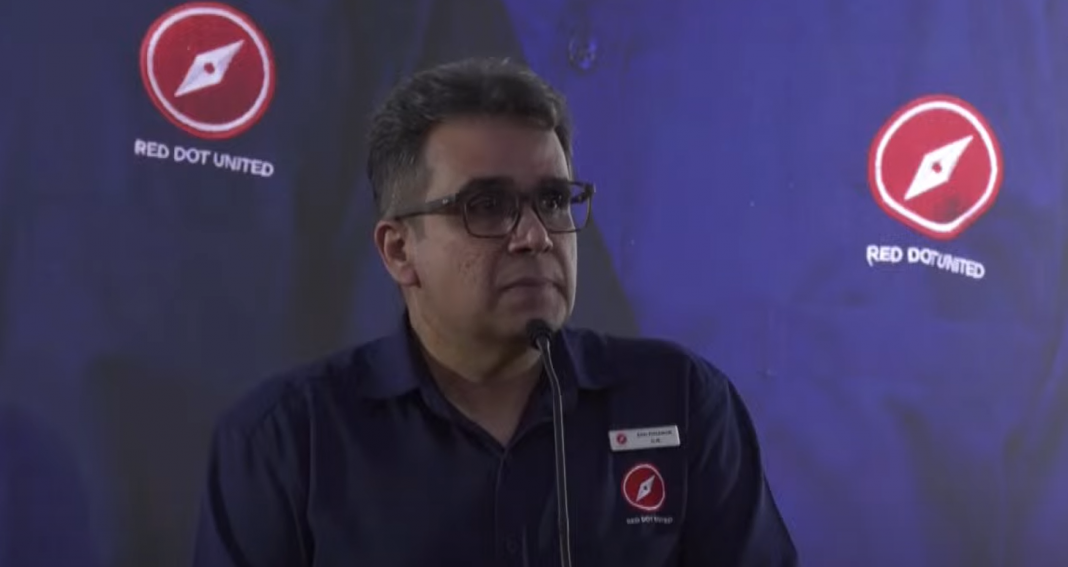

When the RDU chief negotiated for Jalan Kayu, he prioritised two things: who could best serve the people, and how to maintain opposition unity. That is the spirit needed now, more than ever.

The way forward: Lessons from history, hope for the future

When Singapore’s first generation of opposition leaders stood up in the 1980s and 1990s, they faced overwhelming odds. Yet they persevered, and in doing so, they kept alive the flame of democratic choice. Figures like J.B. Jeyaretnam, Chiam See Tong, and later Low Thia Khiang showed that it was possible to win, even against the odds — provided the opposition stayed disciplined, principled, and people-focused.

Disagreements are inevitable. Ideological diversity is healthy. Strategic coordination is no longer a luxury; it is a necessity.

After this election, as Mr Philemon says, we must pick up the pieces. Rebuild trust. Rebuild unity. And it cannot wait until the next election cycle. The work must begin immediately, or there might not be another chance for a very long time.