Every night for the past two weeks, Singaporeans watched as the Committee of Privileges investigated Raeesah Khan, formerly MP for Sengkang GRC and leading members of her former political party, for lying in Parliament.

Is the Committee of Privileges politically motivated? Is this investigation a witch hunt and a prelude to “fix the opposition”?

Why is Raeesah Khan in hot soup with parliament?

On 3 Aug 2021, Raeesah Khan gave a speech in parliament about gender equality. She claimed to have accompanied a victim of sexual assault to the police station, where questioning by the police officers traumatised the victim further. Khan demanded an overhaul in the training of police officers to handle such cases, and for the police force to engage independent, professional counsellors.

Khan was encouraged in parliament on 10 Aug and 4 Oct to provide more details to the police. It took three whole months for Khan to admit in parliament that she had been lying all along.

On 20 Oct, the police announced they turned up nothing in an internal review. It was only on 1 Nov that Khan confessed in parliament her account was a lie. She was traumatised by her own experience (which allegedly took place years ago in Australia) and was recently triggered by similar accounts of other victims in a local “assault survivors group”.

Unimpressed by the lie and the explanation, Indranee Rajah, the Leader of the House, referred the matter to the Committee of Privileges.

The sequence of events plainly shows that Khan lied in parliament, repeated her lies for three months, and a complaint was filed when her lies were exposed, and she admitted her guilt.

But is lying a crime? Can parliament not be so serious?

Procedurally, it all seems above board. A member of parliament may have breached parliamentary privilege, a complaint was filed by the Leader of the House, and the correct committee has been convened to investigate the complaint.

Underpinning the woes of Khan and the Workers Party leaders is the concept of parliamentary privilege.

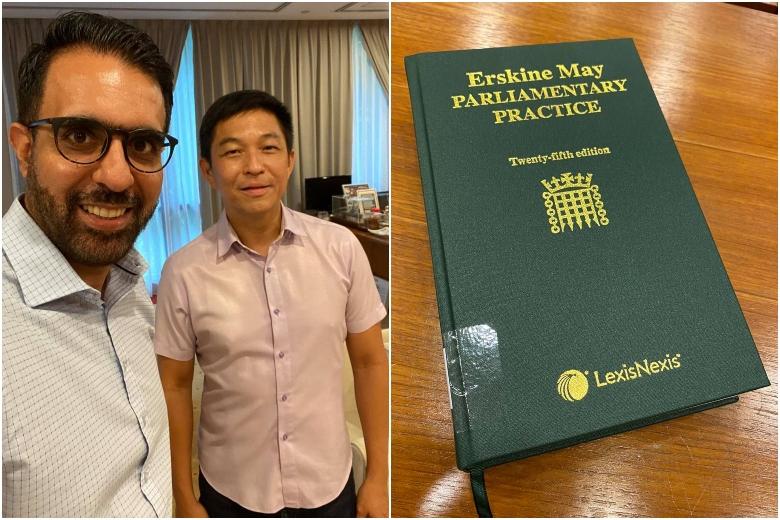

Right: Pritam Singh’s copy of Erskine May, which he should read before appearing to the COP

Singapore inherited its parliamentary system and system of democracy from the United Kingdom. The Parliament (Privileges, Immunities, and Power) Act acknowledges our debt to the mother of parliaments.

The privileges, immunities and powers of Parliament and of the Speaker, Members and committees of Parliament shall be the same as those of the Commons House of Parliament of the United Kingdom and of its Speaker, Members or committees at the establishment of the Republic of Singapore. (Section 3(1))

The preamble to the Act explains that:

There shall be freedom of speech and debate and proceedings in Parliament, and such freedom of speech and debate and proceedings shall not be liable to be impeached or questioned in any court, commission of inquiry, committee of inquiry, tribunal or any other place whatsoever out of Parliament. (Section 5)

This is congruent with what Erskine May sets out in his “Bible of parliamentary procedure“:

Certain rights and immunities such as freedom from arrest or freedom of speech are exercised primarily by individual Members of each House. They exist in order to allow Members of each House to contribute effectively to the discharge of the functions of their House. (Part 2, Cap. 12)

Ordinarily, the parliamentary privilege protects members of parliament and witnesses providing evidence to parliament committees immunity from prosecution. Erskine May explains further that parliamentary privilege can be breached or violated, and such contempt of parliament is subject to penalties imposed only by parliament:

When any of these rights and immunities is disregarded or attacked, the offence is called a breach of privilege and is punishable under the law of Parliament. Each House also claims the right to punish contempts. These are actions which, while not necessarily breaches of any specific privilege, obstruct or impede it in the performance of its functions, or are offences against its authority or dignity, such as disobedience to its legitimate commands or libels upon itself, its Members or its officers. (Part 2, Cap. 12)

Any act or omission which obstructs or impedes either House of Parliament in the performance of its functions, or which obstructs or impedes any Member or officer of such House in the discharge of his duty, or which has a tendency, directly or indirectly, to produce such results may be treated as a contempt even though there is no precedent of the offence. (Part 2, Cap. 15)

How do we know if the committee is doing its job properly?

The proper scope of the committee, which should appear in the preamble of the eventual report to parliament, would be to ascertain if Khan had indeed breached parliamentary privilege, if others had collaborated with her or directed her to do so (under the “abet” clause of the Parliamentary (Privileges Immunities and Powers) Act), the seriousness of the breach, and then to propose the appropriate penalty or penalties.

Following Erskine May’s paragraphs on privilege and contempt, Khan’s lies would be considered a breach of parliamentary privilege if the committee does find that her lies either obstructed or impeded Parliament or its officers in its performance of its functions or lowered the authority and dignity of Parliament or its officers in the eyes of the public.

But in India, a wealth of case precedents and subsequently commentaries on Erskine May and parliamentary philosophy have been developed by the Lok Sabha’s committee of privileges over decades. Most important is this justification for breaches and contempt of privilege to be punished:

It is against the rules of parliamentary debate and decorum to make defamatory statements or allegations of incriminatory nature against any person and the position is all the worse if such allegations are made against persons who are not in a position to defend themselves on the floor of the House. The privilege of freedom of speech can only be secured, if members do not abuse it. – 26th report of the Lok Sabha Committee of Privileges, 1983

Why should the WP leadership be hauled up?

Any person who attempts to contravene any provision of this Act or abets the contravention of any such provision shall be guilty of an offence and shall be liable on conviction to the penalty to which he would have been liable for a contravention of the provision itself.

On her first testimony to the committee, Raeesah Khan revealed an interesting, uncommon, and quite unique practice of the Workers Party: WP MPs vet and comment on each other’s speeches before they are given in Parliament.

She also revealed that her parliamentary colleagues in the party already knew that she had lied by 6 Aug 2021. She also claimed that after seeking advice on the way forward, leaders like Pritam Singh and Sylvia Lim told her, amongst other things, that “It’s your call.”

As she saw it she could, in effect, stop discussing her story in Parliament and say nothing else, and hopefully, there would be no repercussions.

The committee would be right to invite Singh and Lim to give testimony, to ascertain if their advice, by omission or commission, directly or indirectly led Khan to continue lying for 3 months to Parliament.

The wording of the advice would be important, for which any conflicts in testimony and memory can be clarified. Most important, however, is that any advice made by Singh and Lim to Khan can be judged by clear standards:

What is the plain meaning of the words said or written? Would any ordinary person interpret, as Khan did, that she was given leeway to continue to lie or refrain from coming clean?

If Khan had abused her privilege, was she abetted by her party leaders?

Did Khan fall short of standards expected of a member of parliament? Did her party leaders fall short of standards by giving advice that didn’t prevent her from lying, didn’t make her come clean?

Should the committee of privileges care how Pritam Singh conducted his party’s disciplinary committee?

Did Pritam Singh throw Raeesah Khan under the bus?

Why was Khan only disciplined after her lie came to light and resulted in a parliamentary investigation?

Why didn’t Pritam Singh tell his party disciplinary committee the full facts that he and other MPs were aware of the lie, and actively gave counsel to Khan over the three months?

We note that the Lok Sabha’s committee of privileges had this to say in 1987, again developing on Erskine May:

As per the established convention, the Chairman does not take cognizance of what transpires at party meetings.

One may believe from the evidence that has been unearthed from the committee sessions that Singh is the sort of party leader that can be trusted to toss as many inconvenient party members under the bus to fulfil his party narrative.

This is a matter for the party, not the parliamentary committee, as it is outside its scope. The committee may have unearthed this matter but should not use it as evidence to determine any breach of privileges or contempt of parliament.

These revelations are a matter for Singh and the party he leads: party volunteers and potential candidates should take note and make their own decision on this matter.

A version of this article first appeared at https://akikonomu.blogspot.com