By Elvin Ong

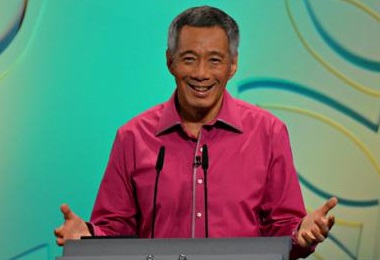

The policy changes in education, housing and healthcare announced by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong in his National Day Rally this year have drawn plaudits from most mainstream commentators for both the substance and the rhetoric. They note how the proposed changes fit squarely with the aspirations articulated by a broad spectrum of Singaporeans in the National Conversation for a slower, kinder and gentler society.

Yet, there are also concerns from some quarters that the proposed changes are populist. Some say that the People’s Action Party (PAP) always focused on implementing policies with a long-term vision in mind for Singapore, and had eschewed short-term populism.

To the extent that such a characterization of PAP in the past is true, we should recognize that ‘populism’ is not necessarily a bad word. What is so wrong about tailoring government policies to benefit the most number of people? Are the ideas of economic growth, inclusive growth, and compassionate meritocracy not ‘populist’ too?

Moreover, it may be useful to view these so-called “populist” changes not just as a direct response to the findings of the National Conversation, but also as a direct result of the PAP’s declining success in elections over the past few years.

To recap, in the General Election of 2011, the PAP scored its lowest vote share since independence and lost Aljunied GRC to the Workers’ Party (WP). In the subsequent Presidential Election in that same year, the PAP’s endorsed candidate Tony Tan won with the slimmest of margins – just 0.35% of valid votes ahead of Tan Cheng Bock. In the Hougang by-e

lection in 2012, the PAP’s Desmond Choo once again lost to the WP candidate, Png Eng Huat. And finally, in Punggol East earlier this year, WP’s Lee Li Lian triumped over PAP’s Koh Poh Koon with a more than 10% margin.

These successive setbacks in the electoral arena for the PAP were a clear signal from the electorate to the PAP that they no longer agreed with its previously stagnant policies. Either shape up, or ship out.

The Minister for Environment and Water Resources Vivian Balakrishnan was absolutely right when he said, “Politics is about power.” When the PAP loses elections, its power diminishes. To regain power, it must win elections. And to win elections, it must win votes. And to win votes, it must change its policies both in substance and in rhetoric. Whether these changes are significant and substantive enough is up to the electorate to judge.

From this view, then, my point is that the PAP, as like all other political parties, have always been populist parties at the onset because they seek to maximize their votes. They are as populist now as they are in the past. Ironically, no matter how much PAP politicians may demonize populism or say they disregard public opinion in the past, they do so in order to pander to populism.

Overall, this politics-policy link that we have observed harbour signs of the growth of an enlightened democracy at its very best. The electorate knows what it wants and does not want, and is not afraid to signal its preferences. Political leaders take the electorate’s grievances seriously and work hard to address them. Now, time for the democratic institutions to catch up.

At the end of the day, the key lesson is this: Singaporeans must surely begin to see how their vote, if they can coordinate, can bring about the changes that they desire. It is certainly not a cliché to say that their destiny lies in their own hands.

Elvin Ong is a graduate of Singapore Management University and holds an MPhil in Politics (Comparative Government) from the University of Oxford. He is currently a PhD graduate student in the Department of Political Science at Emory University.