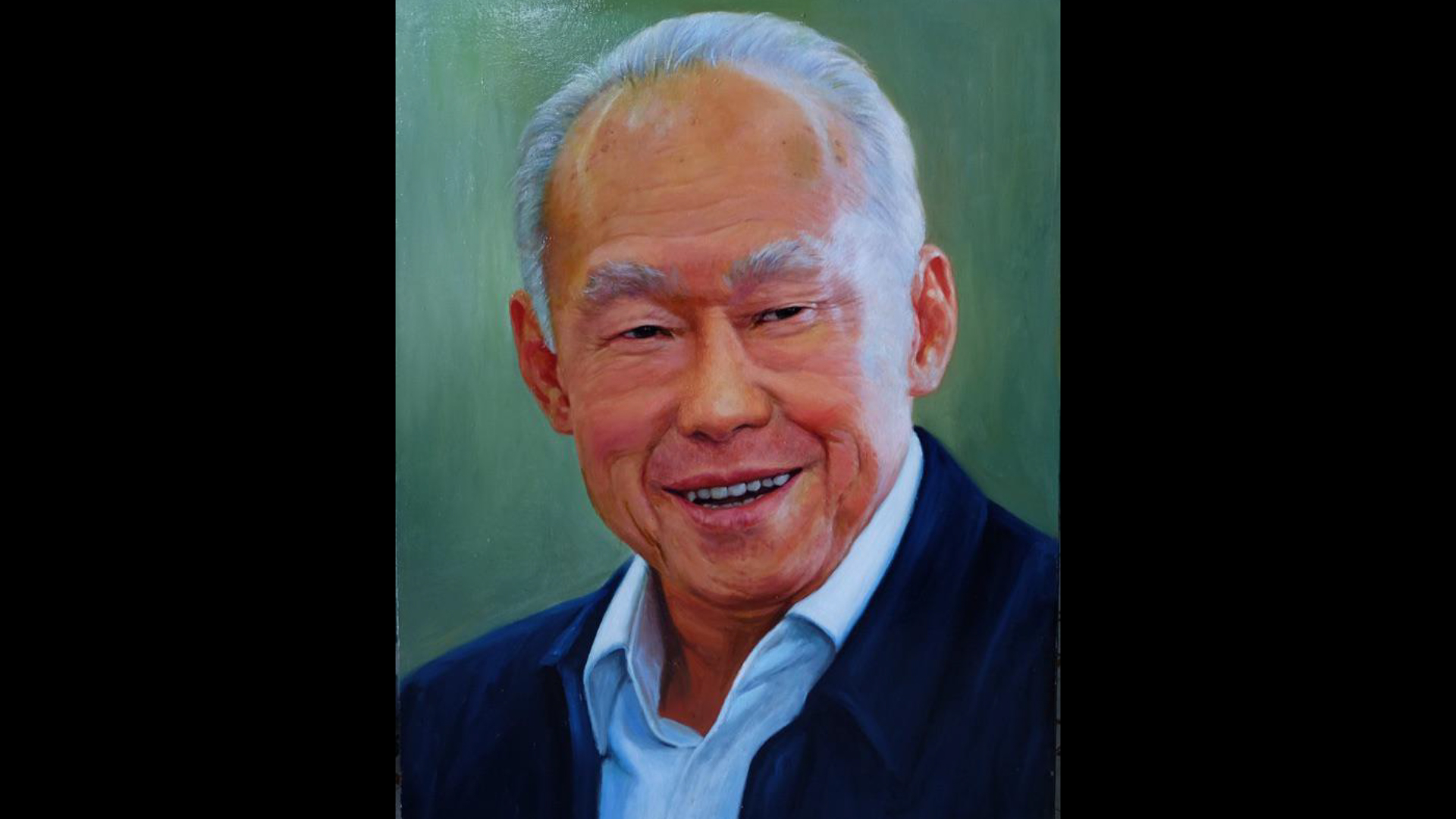

“Lee Kuan Yew understood power. I often felt that in any relationship or interaction, his first consideration was relative power,” said George Yeo in his book Musings Series Three.

“Lee Kuan Yew was intimidating. While he understood power and how to use power, it was also important for him to win the intellectual and moral argument. One would not take Lee Kuan Yew lightly,” said Yeo in his book.

“I learnt much from Lee Kuan Yew. Sometimes I felt like a magician’s assistant watching his master perform,” wrote Yeo.

From 1991 to 2011, Yeo was Singapore’s foreign minister, minister of trade and industry, health minister and minister of information and the arts. During that period, Lee had already retired as the first prime minister of Singapore and assumed the titles of senior minister and, subsequently, minister mentor.

Lee Kuan Yew said intelligence was unevenly distributed, Yeo’s book recalled. “He also emphasised that, in wartime, it was critical that SAF officers like us were giving the orders rather than being given orders by less intelligent officers. Lee Kuan Yew never hid his views about human intelligence, its genetic transmission and rule by a meritocratic elite.”

“On one issue, I did not have the courage to contradict him. It was about his views on genetics and the importance of pedigree. I was sorely tempted to argue that in a time of social breakdown, mongrels survived best, but never did,” Yeo recounted in his book.

Presumably, what Yeo implied was mongrels carried the genes of different breeds and grew up in a rougher environment, so they were tougher and knew how to adapt to changing and difficult situations.

“Lee Kuan Yew had a gift which all politicians wish they have, which is to have a sense of their own people. Even after being PM (Prime Minister) for many years, he had a keen nose for what’s important to ordinary Singaporeans. I noticed he treated Istana staff and his security officers with respect,” Yeo wrote.

In a discussion on enforcing the wearing of crash helmets, Lee commented that many motorcyclists in Singapore were Malays, he added. “A bad crash would rob an entire family of a breadwinner. It was unconscionable. There was an emotion to his argument which gave it force.”

Foreign relations

“I saw the way Lee Kuan Yew interacted with many foreign leaders. The conversations were never perfunctory. He always did his homework,” wrote Yeo, who was Singapore’s foreign minister from 2004 to 2011.

With leaders of big powers, Lee Kuan Yew held his own and was often able to provide helpful views, Yeo’s book recalled. “He was utterly realistic about Singapore’s utility to other countries and never went beyond what was possible or credible.”

With Chinese leaders in private settings, Lee Kuan Yew was quite open in expressing Singapore’s cultural affinity, the book said. “However pro-US Singapore might seem to be, Chinese leaders knew that Lee Kuan Yew was convinced that China’s re-emergence on the global stage was good for Singapore’s own future.”

Lee Kuan Yew enjoyed high access to US Presidents when he was Singapore’s Prime Minister from 1965 to 1990, Yeo wrote. “During my time, it was clear that George Bush Sr valued his advice. Once Lee Kuan Yew stepped down as Prime Minister, his access to the White House was limited.”

Lee Kuan Yew’s relationship with the late Indonesian President Suharto was so close that former Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad wondered if Lee Kuan Yew spoke Javanese, given Suharto was Javanese, Yeo’s book said. “Lee Kuan Yew did not. But he did behave in a Javanese way on the one or two occasions I accompanied him when he called on Suharto. Neither made a point too strongly. Gentle indications of agreement or disagreement were sufficient between the two men. The smile never left their faces.”

“Lee Kuan Yew was able to adjust himself to the culture of his interlocutor. With Australians, he could be as forthright as them. Once when he called on the Sultan of Kedah in 1990, I saws him bowing lower than normal. He knew what pleased Malay royalty,” Yeo’s book recounted.

“I never saw Lee Kuan Yew subordinating himself to anyone except Tunku Abdul Rahman,” Yeo’s book recalled.

“At the end of 1989, I accompanied Lee Kuan Yew on his farewell call as PM to Malaysia. In Penang, he and Mrs Lee called on the Tunku and his wife, both of whom they had not met since Separation (of Singapore and Malaysia in 1965). Tunku was virtually blind and stood at the door to welcome Mr and Mrs Lee with dark glasses on. It was an emotional meeting. Tunku slumped back on a sofa while Lee Kuan Yew sat on the edge. Just about every sentence either began or end with Tunku. Yes, Tunku. No, Tunku. But Tunku, you remember….” The book related.

In his younger days, Lee cultivated Tunku Abdul Rahman, who was Malaysian prime minister from 1957 to 1970, over many years to get Singapore’s independence through a merger with Malaysia, the book explained.

What others thought of Lee Kuan Yew

After losing Singapore’s general elections in 2011, Yeo moved from Singapore to Hong Kong to work for Kerry Logistics, a Hong Kong-listed logistics company controlled by Malaysian tycoon Robert Kuok.

“While working with Robert Kuok in Hong Kong, he told me many stories about Lee Kuan Yew and was happy to hear mine,” Yeo recounted in his book.

“Although I learned new things about Lee Kuan Yew, both good and not so good, I was not really surprised. Great men have their foibles,” Yeo said in his book.

Robert Kuok is both fond and critical of Lee Kuan Yew, Yeo added. “One day he asked me to compare Lee Hsien Loong to his father. I replied that Lee Kuan Yew played a wide keyboard. While Lee Hsien Loong did not play as wide a keyboard, on parts of it, he played better than his father. Robert Kuok did not press further.”

“Despite their previous political clashes, there was dignity in the way Lee Kuan Yew and David Marshall interacted with each other,” the book said.

The late Marshall was Singapore’s chief minister during the 1950s.

“Marshall told me that each had qualities the other wished he had. He thought Lee Kuan Yew did not prepare legal cases as well as he did but was quick enough to absorb new information in court and incorporate them into his argument. He wondered whether Lee Kuan Yew was ever unserious and mused whether he was one to ever potter around in his room doing little things. But I could see that Marshall had tremendous respect for Lee Kuan Yew and was proud of what he did for Singapore,” Yeo said in his book.

Toh Han Shih is chief analyst of Headland Intelligence, a Hong Kong risk consulting firm