The question was asked one night in 2010. An important member of the Old Guard — Goh Keng Swee — had passed away, and I was among the Today journalists who were processing the news for the next day’s newspaper.

The question, asked gently, was: “Who is he?” It was posed by a computer engineer who was on duty in the newsroom.

I paused for a moment and replied that Goh had been an important member of the country’s early government. I asked him equally gently whether he was a Singaporean. He was. I then asked his age. He was 26. I added that Goh had left the government years earlier. A check later showed that Goh had left in 1985 when the computer engineer was only a year old. And Goh had not been much in the news after that.

There are all kinds of reasons for someone not to have such information, although access is probably much easier now because of the development of the Internet and news websites. And the increasing use of electronic devices like laptops and handphones over the years to check for information.

In the past, the lack of this information on the part of the individual could have been because of the limited focus on local history in the school syllabus. It could also be that there may have been a paucity of written material on the subject.

So, more and more it will become, not the availability of information on a subject, but rather arousing interest in it. And all of us have different interests. Do we, therefore, merely accept that we are all different and that when we don’t know something, it does not mean that we don’t care or that we are less intelligent? Perhaps when this happens, the party which has the information should just give it. The person who does not know it can then easily get details and much more from the internet, through his laptop or handphone.

Over the years, this lack of knowledge, especially of local history for one reason or another, has been highlighted by some of our country’s leaders and at least one top bureaucrat.

Whatever it is, historians and layman writers need to continue with their work of recording the past … and welcome questions from those who are curious about anything or anyone in the news.

These questions may, however, become fewer and fewer as man moves into the future. This lack of immediate knowledge. A person may not know something off-hand, but he will easily learn a lot about it in seconds. So the problem is not the access to information, but the availability of it.

As for the original port in Tanjong Pagar and the Tanjong Pagar and Anson portside, while there have been publications about the port commissioned by the various authorities, there is a need for more material to be compiled and published about the portside. This is a historic part of modern Singapore. All the more so because the original port is no longer there, as following its transformation from a conventional to a container operation, it has been moving west, with the final destination being Tuas.

The original location, which had hillocks along the coast that were levelled to provide earth for the reclamation work for the port, is now empty and silent. It is awaiting redevelopment. It is as empty and silent now as it was when Raffles arrived in 1819. More than 200 years ago.

There have over the years been some Facebook and other posts about the portside, but the important basic information is not always there. For example, the name of the street in which something happened or the year in which it happened.

There is also a need for posts to be accurate. One post, for example, had a small map that had the street alignments wrong. This is because, on the Internet, there are none of the usual editing checks.

I have tried, with much help from people familiar with the port and portside, to shed more light on this early area of the history of modern Singapore. We have focussed on life there and put up a structure to which much more information can be added, especially of the earlier years from the time of the arrival in 1819 of Raffles, who is acknowledged as the founder of modern Singapore. There is some information in my book from that time on the port until the change in its operations from conventional to container from the mid-1960s onwards, the expansion of which necessitated the demolition of rows of pre-war buildings and the relocation of tens of thousands of people.

A landmark that was demolished was the Boustead Institute building, at the corner of Tanjong Pagar Road and Anson Road, which provided accommodation for thousands of sailors from 1898 till 1958. A bar was set up there that year, and it has a curious story behind it. It was closed suddenly by the authorities the following year. No reason was given. It had been set up by a former Nigerian sailor and his Shanghai wife. He had, seeing a business opportunity in Singapore because its port was at the crossroads of the world, set up the eponymous Toby’s Paradise Bar, but it could last barely a year.

Other buildings hit were a ship’s laundry that held a spectacular firecracker event. There were also two police stations with the same name but for different purposes in the area — Tanjong Pagar Police Station. The stations with the same name also suffered the same fate, being demolished for the expansion of the container port.

Much more can be written about the area, but records may not have been kept properly. Sometimes the staff in an organisation about which information is sought do not know much about its history or do not know how or where to locate the information.

However, everyone must soldier on.

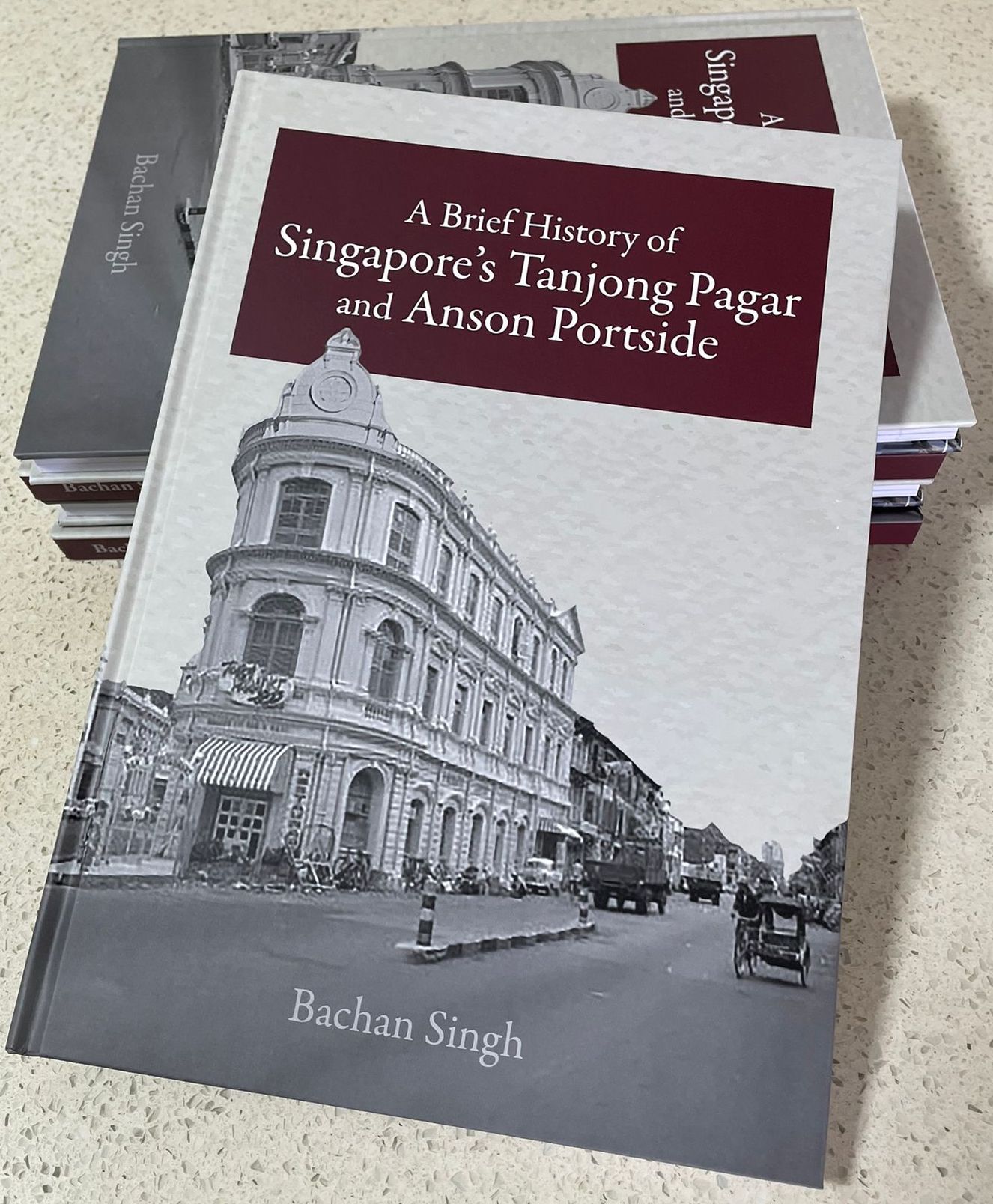

The book A Brief History of Singapore’s Tanjong Pagar and Anson Portside (hardcover) is available at the Epigram Bookshop. An e-book is also available. (Kindle/Amazon).

Book Review: A Brief History of Singapore’s Tanjong Pagar and Anson Portside