The big news story so early in the year began with a young couple who got scammed out of a huge sum of money in a “phishing scam” targeted at OCBC customers. The details of the story can be found here:

There was something of a kerfuffle over what banks should be liable for. The end result was that banks in Singapore started sent out even more warnings about scams and listing the precautions customers should take and promising that that they were protecting their customers.

Scams and con jobs are nothing new. Con jobs have been around since there have been jobs. As human civilization has “advanced” so have scams and con artists. This has been particularly true as technology has advanced to levels once considered futuristic.

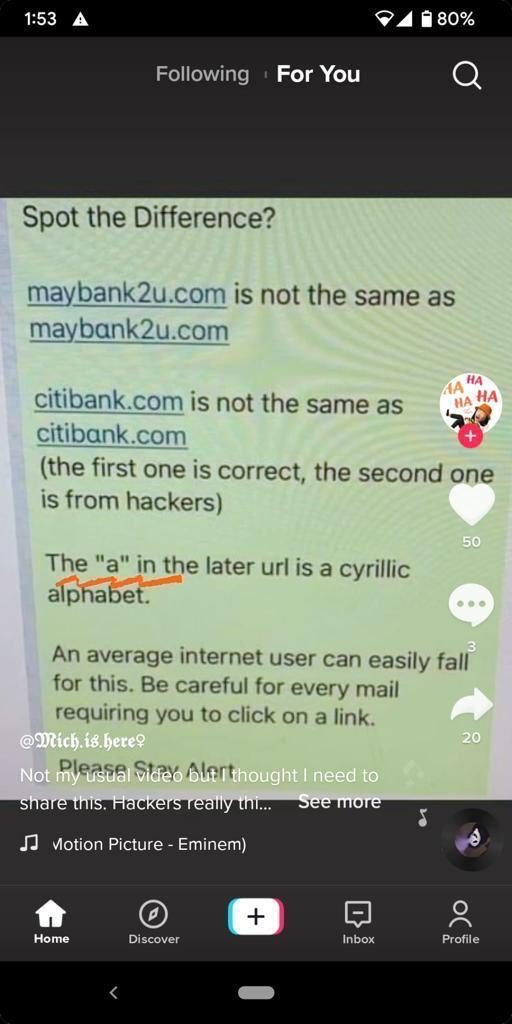

The level of phishing scams has become so sophisticated that the average person is not going to be able to tell between a message from a scammer and one from the actual institution being impersonated. See this example below:

I guess if you have to be fair to scammers, the guys who create the sophisticated scams actually work very hard to create something that most people wouldn’t be able to recognise as a scam. How, for example would an untrained eye be able to distinguish between the real bank and the scammers’ creation when the difference in the URL is ever so slight?

However, a lot of scams aren’t all that difficult to spot if you are sharp enough. The scam letters out of Nigeria are usually the easiest to spot. In some cases, the letters from the respective ministries don’t even bear the letterhead of the ministry they purport to represent. One of my favorites was a supposed diamond dealer whose “bank statements” purporting to be from a bank in Macau looked like they had been printed on an Excel sheet

As unsophisticated as these traps are, the question remains – if such scams are easy to spot, how is it that they continue to flourish. Well, the answer is pretty obvious: they thrive because they have an endless source of customers.

People continue to fall for them because the scams do have a veneer of credibility and they appeal to people’s greed. It’s the second factor that usually screws up a victim. Speak to a victim and he’ll likely tell you there were “NO REASONS NOT TO TRUST.” So, what are these “NO REASONS NOT TO TRUST”?

One of the more sophisticated ones that comes to mind involved getting mid-level professionals to invest in hydroponic farms. It sounded credible. The government (usually the source of everything in Singapore) had been talking about food security and not depending on imports and the science of hydroponics has been proven. So, in that respect the premise was credible.

However, the key issue was that it was more “talk” about hydroponics than actual hydroponics. The scam artist in question was very generous producing glossy brochures and held impressive seminars for “investors”. However, this was hype with no substance. Even the photos on the glossy brochures turned out to be stock photos from the “royalty-free” section of a stock library.

The scam’s premise was actually credible. The presentation was incredibly slick. On paper there was nothing to fault the prospective investors .

Another way scammers take to gain the trust of victims is to use “trusted people”. One of the saddest cases that comes to mind was that of an “investment” house that claimed to be lending money to banks that offered higher interest rates.

In this case, the premise sounded improbable. But it turned out that the main scammer was the kind of person the targets were inclined to trust – specifically a well-established working professional. He introduced his victims to two young men, who behaved like “nice boys” as they proceeded to fleece a group of pensioners out of their life savings (which were promptly funnelled to Mauritius, India and St Lucia).

If you ask every victim why they parted with their money, you’ll probably find that the answer being “I had NO REASON NOT TO TRUST.” I think of one of the victims telling the director of the company that scammed him – “You are my niece – you should have stopped me from putting in the money in October when you knew the company would have to close its bank account in December.”

Ask any of the victims of this scam and they are likely to tell you that they had “NO REASON NOT TO TRUST,” the people that they were talking to because they were either “nice” or a “relative” or a “friend.”

In a way, Singaporeans have been lucky. We are one of the best educated people on the planet. However, we tend to fall for things easily because we’ve been trained to trust certain things. How can, for example, established working professionals be untrustworthy – after all they are all licensed and regulated by the state? How can anyone who spent so much on a marketing campaign be a crook? We have been trained to believe that anyone who wears a shirt (especially a white, pressed one) has our interest at heart.

Crooks and conmen are not unique to Singapore. However, in a culture where signs and symbols of material wealth are equated with virtue and skepticism towards established authority is frowned upon, you provide a fertile ground for con artist. When someone shouts “Trust me!” you had better not.