SINGAPORE: Researchers at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore (NUS Medicine), have uncovered crucial insights into how cells maintain their health by recycling vital fat molecules, potentially opening new doors for treatments for rare genetic diseases.

Their study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), focuses on the role of a protein, Spinster homolog 1 (Spns1), in transporting fat molecules out of cell compartments known as lysosomes—the cell’s “recycling center.”

The team, led by Associate Professor Nguyen Nam Long from the Department of Biochemistry and Immunology Translational Research Programme (TRP) at NUS Medicine, discovered that Spns1 functions as a cellular gatekeeper, specifically helping to move lysophospholipids—types of fat molecules—into the lysosome. There, they are recycled and reused for various essential cell functions.

This recycling process is vital in preventing harmful fat accumulation, which could otherwise damage cells.

“Our research sheds light on how Spns1 ensures fats are properly recycled, preventing diseases that arise from fat buildup in cells,” said A/Prof. Nguyen. “This insight could be critical for developing treatments for diseases where Spns1’s function is impaired.”

The recycling of fats in cells occurs via three primary pathways: endocytosis, phagocytosis, and autophagy. In endocytosis, the cell engulfs external materials within vesicles, transporting them to the lysosome for breakdown. Immune cells such as macrophages perform phagocytosis, ingesting large particles like pathogens or damaged cells and directing them to lysosomes. Autophagy, on the other hand, allows cells to self-clean by engulfing damaged internal components, such as old mitochondria, and sending them to the lysosome.

Once inside the lysosome, fats are broken down into essential components that support various cell functions. These include membrane repair and maintenance, energy production, and cellular communication. Fat-derived molecules like sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) are involved in key processes like cell growth, movement, and survival, ensuring the body’s organs and systems operate efficiently.

Spns1’s role is particularly crucial in avoiding a condition known as lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs), which are a group of over 50 rare genetic disorders that occur when the lysosome fails to break down and recycle molecules properly. Disorders such as Gaucher, Tay-Sachs, Niemann-Pick, and Pompe disease result from the accumulation of lipid waste inside cells. Dysfunction in the lysosomal recycling pathway is also implicated in neurodegenerative conditions like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases.

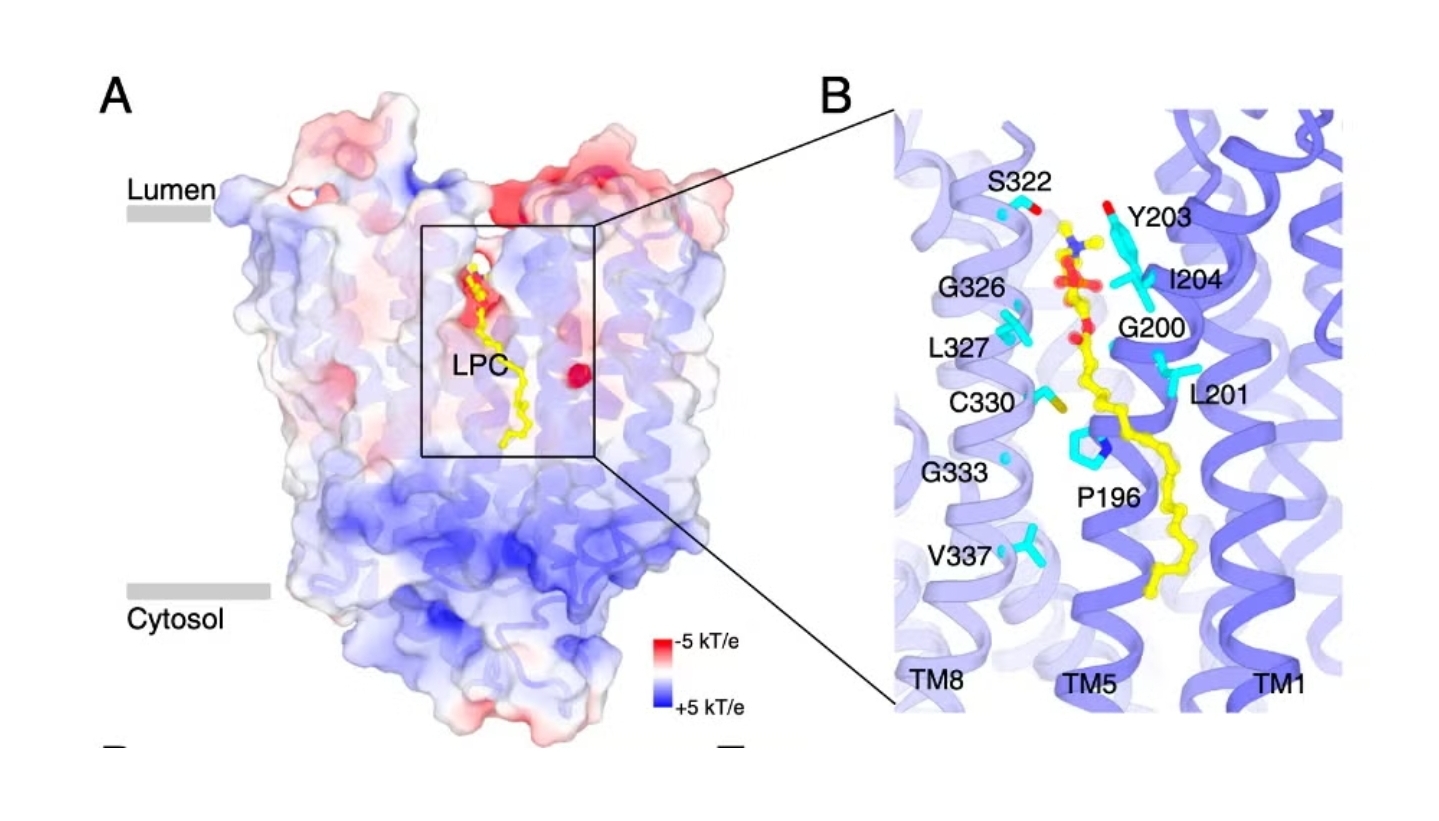

Collaborating with Professor Xiaochun Li’s team from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UTSW), the researchers used advanced cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) to capture detailed images of Spns1 interacting with lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), a specific lysophospholipid. These images provided a deeper understanding of how Spns1 senses cellular conditions and regulates fat transport.

The researchers also identified the specific parts of Spns1 essential for its function, confirming that the protein’s gate-like action is key in moving fats out of lysosomes. This process is regulated by signals from the cell’s environment, ensuring fats are transported only when needed. Mutations in Spns1 can disrupt this balance, leading to the accumulation of waste inside cells and contributing to various diseases.

As part of ongoing research, the team is studying Spns1’s opposite state—how it releases fats from the lysosome to the rest of the cell. Understanding this complete transport cycle is vital for designing effective therapeutic interventions.

By leveraging these findings, the team hopes to develop targeted treatments for LSDs, which could significantly improve the lives of patients affected by these debilitating conditions.