Andrew King, University of Melbourne and David Karoly, University of Melbourne/

The year isn’t over yet, but we can already be sure that 2017 will be among the hottest years on record for the globe. While the global average surface temperature won’t match what we saw in 2016, it is now very likely that it will be one of the three warmest years on record, according to a statement issued by the World Meteorological Organization.

What is more remarkable is that this year’s warmth comes without a boost from El Niño. When an El Niño brings warm waters to the tropical east Pacific, we see a transfer of heat from the ocean to the lower atmosphere, which can raise the global average temperatures recorded at the surface by an extra 0.1-0.2℃. But this year’s temperatures have been high even in the absence of this phenomenon.

We can already say with confidence that 2017 will end up being the warmest non-El Niño year on record, and that it will be warmer than any year before 2015. The average global temperature between January to September this year was roughly 1.1℃ warmer than the pre-industrial average.

This trend is associated with increased greenhouse gas concentrations, and this year we have seen record high global atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations and the biggest recorded surge in CO₂ levels.

A year of extremes

Of course, none of us experiences the global average temperature, so we also care about local extreme weather. This year has already seen plenty of extremes.

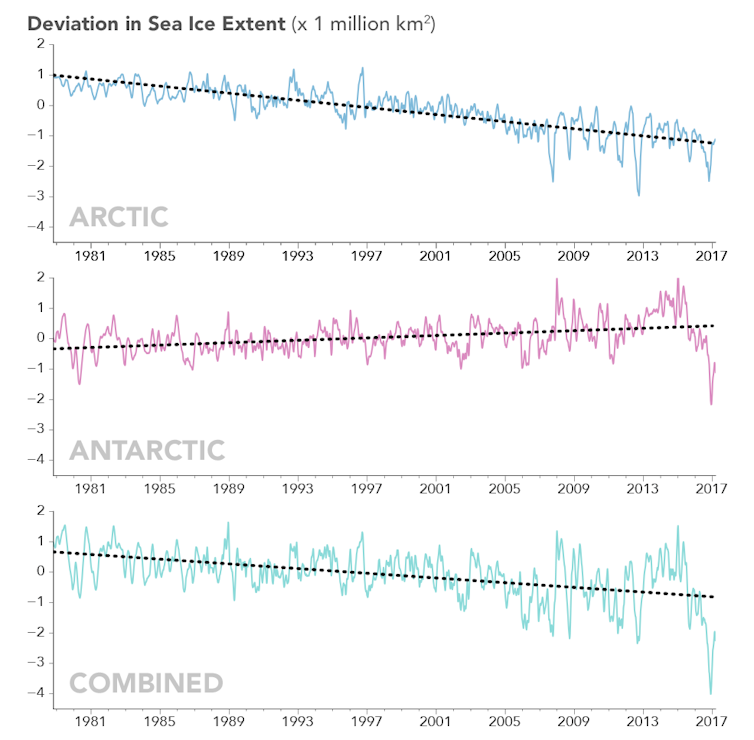

Global sea ice extent continues to decline.

NASA Earth Observatory

At the poles we’ve seen a continuation of the global trend towards reduced sea ice extent. On February 13, global sea ice extent reached its lowest point on record, amid a record low winter for Arctic ice. Since then the Arctic sea ice extent has become less unusual but it still remains well below the satellite-era average. Antarctic sea ice extent also remains low but is no longer at record low levels as it was in February and March of this year.

East Africa saw continued drought with failure of the long rains, coupled with political instability, leading to food insecurity and population displacement, particularly in Somalia.

Storms and fires

This year also saw a very active North Atlantic hurricane season. Parts of the southern United States and the Caribbean were struck by major hurricanes such as Harvey, Irma, and Maria, and are still recovering from the effects.

Other parts of the globe have seen a quieter year for tropical cyclones.

There have also been several notable wildfire outbreaks around the world this year. In Western Europe, record June heat and very dry conditions gave rise to severe fires in Portugal. This was followed by more severe fires across Spain and Portugal in October.

Parts of California also experienced severe fires following a wet winter, which promoted plant growth, and then a hot dry summer.

Australia is now gearing up for what is forecast to be a worse-than-average fire season after record winter daytime temperatures. A potential La Niña forming in the Pacific and recent rains in eastern Australia may reduce some of the bushfire risk.

The overall message

So what conclusions can we draw from this year’s extreme weather? It’s certainly clear that humans are warming the climate and increasing the chances of some of the extreme weather we’ve seem in 2017. In particular, many of this year’s heatwaves and hot spells have already been linked to human-caused climate change.

For other events the human influence is harder to determine. For example, the human fingerprint on East Africa’s drought is uncertain. It is also hard to say exactly how climate change is influencing tropical cyclones, beyond the fact that their impact is likely to be made worse by rising sea levels.

![]() For much of 2017’s extreme weather, however, we can say that it is an indicator of what’s to come.

For much of 2017’s extreme weather, however, we can say that it is an indicator of what’s to come.

Andrew King, Climate Extremes Research Fellow, University of Melbourne and David Karoly, Professor of Atmospheric Science, University of Melbourne

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.