SINGAPORE: Former presidential candidate Tan Kin Lian has come out in support of allowing students to use generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools in schools, describing them as valuable aids that can improve learning outcomes when used responsibly.

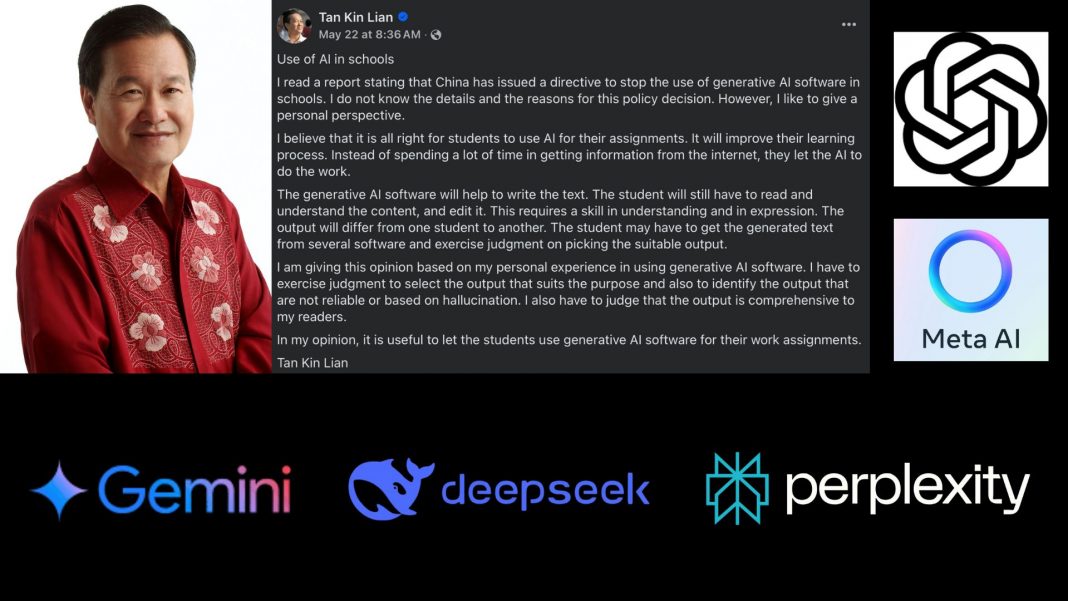

In a Facebook post published on May 22, Tan responded to reports that China’s Ministry of Education had issued new directives restricting the use of generative AI in classrooms. While China’s policy focuses on tightening oversight, particularly at the primary level, Tan offered a more open approach.

“Instead of spending a lot of time getting information from the internet, they let the AI do the work,” he wrote. “The student will still have to read and understand the content and edit it. This requires skill in comprehension and judgment.”

Tan, who previously served as CEO of NTUC Income and ran in the 2023 presidential election, shared that his views are informed by his own experience using AI tools. He explained that reviewing and refining AI-generated outputs demands discernment—a process he believes students can learn from.

“I have to exercise judgment to select the output that suits the purpose,” he added, noting that generative AI systems can sometimes produce inaccurate or incomplete information.

His comments come shortly after China rolled out two key documents: the Guidelines for AI General Education in Primary and Secondary Schools (2025) and the Guidelines for the Use of Generative AI in Primary and Secondary Schools (2025). Together, these aim to build a comprehensive AI education framework while imposing guardrails around how AI can be used in the classroom.

Under the new Chinese guidelines, primary school students are prohibited from independently using open-ended generative AI tools, such as chatbots or content generators. Teachers, too, are barred from relying on AI to perform core duties like answering student questions or grading assignments. They are also instructed to avoid inputting sensitive data into AI systems, a move aimed at safeguarding privacy and reducing dependency.

At the same time, China’s approach does promote AI literacy, using a tiered curriculum that evolves from basic exposure in primary school to systems-level thinking in senior high school. The Ministry of Education has described the move as a step toward cultivating talent equipped with both technical skills and social responsibility in an age of intelligent technologies.

Tan’s position offers a counterpoint to this cautious model. Rather than limiting access, he argues for empowering students to use AI as part of their learning journey, underlining that tools like these can support understanding, not replace it.

His remarks add to a growing global conversation about AI’s place in education. While some governments restrict its use over concerns about misinformation and academic integrity, others—including educators and technologists—continue to explore how the technology might be responsibly integrated into classrooms.

“In my opinion, it is useful to let the students use generative AI software for their work assignments,” Tan said.