2012 marked the seventieth anniversary of beginning of Second World War in South-east Asia and the fall of Singapore to Japanese in February, 1942. The government commemorated this by organising various memorials, trails and ceremonies for educating the younger generation about the War. Few months back, the issue came to light again when Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong on a visit to Tokyo spoke of his experience of mass grave sites of Sook Ching massacre being uncovered in 1962.

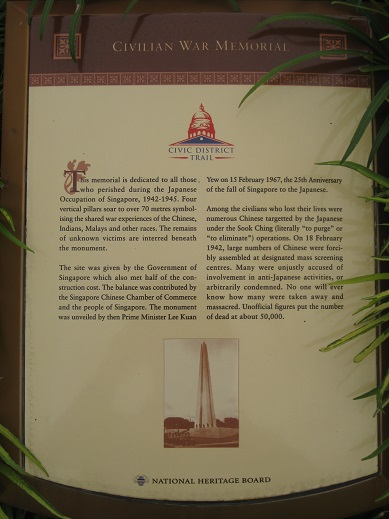

The National Heritage Board’s (NHB) placard at the Civilian War Memorial

Sook Ching massacre

Sook Ching massacre, as it came to be known, was carried out by the Kempeitai (Japanese military police) to screen and eliminate anti-Japanese elements in Singapore during the Occupation. The National Heritage Board’s (NHB) placard at the Civilian War Memorial, which is dedicated to all those who perished during the Japanese Occupation of Singapore between 1942-1945 states, ”Among the civilians who lost their lives were numerous Chinese targeted by the Japanese under the Sook Ching (literally to ‘purge’ or ‘to eliminate’) operations. On 18 February 1942, large numbers of Chinese were forcibly assembled at designated mass screening centres. Many were unjustly accused of involvement in anti-Japanese activities, or arbitrarily condemned. No one will ever know how many were taken away and massacred. Unofficial figures put the number of dead at about 50,000.” As detailed in recently-released NHB’s World War II heritage trail brochure the Kempeitai used the roads in the vicinity of Hong Lim Complex as a Sook Ching registration centre, where Chinese men between the ages of 18-50 were summoned and subjected to prolonged mass screenings. Those who “failed” the screenings were taken to remote beaches for execution – three prominent ones were in Punggol, Sentosa and Changi. The largest massacre site was the Siglap area in the eastern part of Singapore, where five mass war graves were exhumed in 1962. This became an urgent issue in post-War Singapore leading to a demand by the Chinese Chambers of Commerce for a Chinese-style monument to honour the victims.

One of those sites was besides his school, which had bodies of people killed during the Japanese Occupation, Lee noted, while adding,” One factor which colours Japan’s relationship with many of its neighbours is the history of the Pacific War. After the war ended, Japan did not fully reconcile its relations with the countries it had invaded. For many years this unresolved issue made it difficult to build trust and confidence. Prime Minister Murayama’s formal apology in 1995 was thus an important step in helping Japan put the history of the war behind it.”

Lee’s comments come at a time when Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has time and again defended the right of Japanese leaders to visit the controversial Yasukuni shrine and pay respect to the country’s war dead on August 15, which marks the anniversary of the end of Second World War.

Japan is not the only country which can be accused of practising “selective amnesia” about its War time history, as Singapore too had an interesting turn of events in relation to its War memories. Kevin Blackburn, associate professor of humanities at National Institute of Education in Singapore, elaborates in his book, War Memory and the making of modern Malaysia and Singapore.

“Ironically, then, the same Singapore whose government sought to dampen and control war memory in the 1960s, would enter the 21st century with a proliferation of museums, plaques, memoirs, and media productions about the War,” he writes.

Blackburn explains that Singapore’s War memory in the 1960s was successfully harnessed by the People’s Action Party (PAP), when Chinese Chambers of Commerce demand for a Chinese-style monument to honour Sook Ching massacre victims resulted in the Civilian War Memorial at the Beach Road depicting common suffering. “One of then PM Lee Kuan Yew’s motives for harnessing wartime emotions had been to avoid interference with investment,” he writes. The government even adopted a ‘Learn from Japan campaign’, though much to dismay of some of PAP’s own members of the wartime generation, Blackburn adds.

But things started changing in 1980s triggered by the 1982 textbook controversy, in which Japan was revealed as unrepentant about its wartime atrocities by attempting to expunge the portion from its history books. Singapore reacted too and the government here introduced the first official history textbook in 1984 detailing the Japanese Occupation of Singapore. Importantly, Blackburn adds,” By the 1990s, Singapore had a mixture of foreign investment and was no longer heavily dependent on Japanese capital, as in 1970s.”

Thus, the fiftieth anniversary commemorations in 1992 witnessed for the first time a Singapore television documentary Between Empires, which depicted wartime atrocities with focus on Chinese as victims. This was followed by the Chinese-language television series Heping De Dai Jia in 1997, which was based on the history book of the same name published in 1995 by the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Even February 15 – designated as Heritage Day in 1992 – was re-designated as Total Defence Day in 1998. Some schools and Fort Siloso on the Sentosa Island staged mock Japanese attacks to teach children about war-time atrocities.

The NHB did its part too. It identified fourteen war sites and unveiled permanent plaques on them in 1995 to mark the significance of the sites in relation to the War. Six more were added last year in February, as part of NHB’s effort to commemorate the seventieth anniversary of the Fall of Singapore. The NHB now organises a Second World War heritage trail through 50 war sites (including 20 with permanent plaques) including the Sook Ching massacre sites.

The Civilian War Memorial has four parallel pillars that taper together at the top. The pillars signify the four major ethnic groups in Singapore – Chinese, Malays, Indians and Eurasians, and the joining near the top represents unity and shared suffering. Unveiled by the then PM Lee Kuan Yew on February 15, 1967, the 222-foot high structure is a also burial chamber that contains the remains of many of the unidentified victims of Sook Ching massacre. Ceremonies are held every year at the Memorial on February 15 to remember and honour the victims.

Blackburn claims in his book that the approach taken by the Singapore government sought to impose a unified, and unifying national story of common wartime suffering into an embryonic nation. “But the myth-making and unifying approach had its costs. Hence, the retelling of the Sook Ching story through the Civilian War Memorial resulted in that site’s core nature (as a burial place for thousands of overwhelmingly Chinese massacre victims) being downplayed. By making it a largely abstract design of four pillars dedicated to the dead of all communities, its value as an emotional symbol of real and specific massacres was weakened. The therapeutic value and emotional force of sites and ceremonies has thus lessened in Singapore, even as their unifying utility has been enhanced by state re-narration of events and their meaning,” he concludes.